Commentary

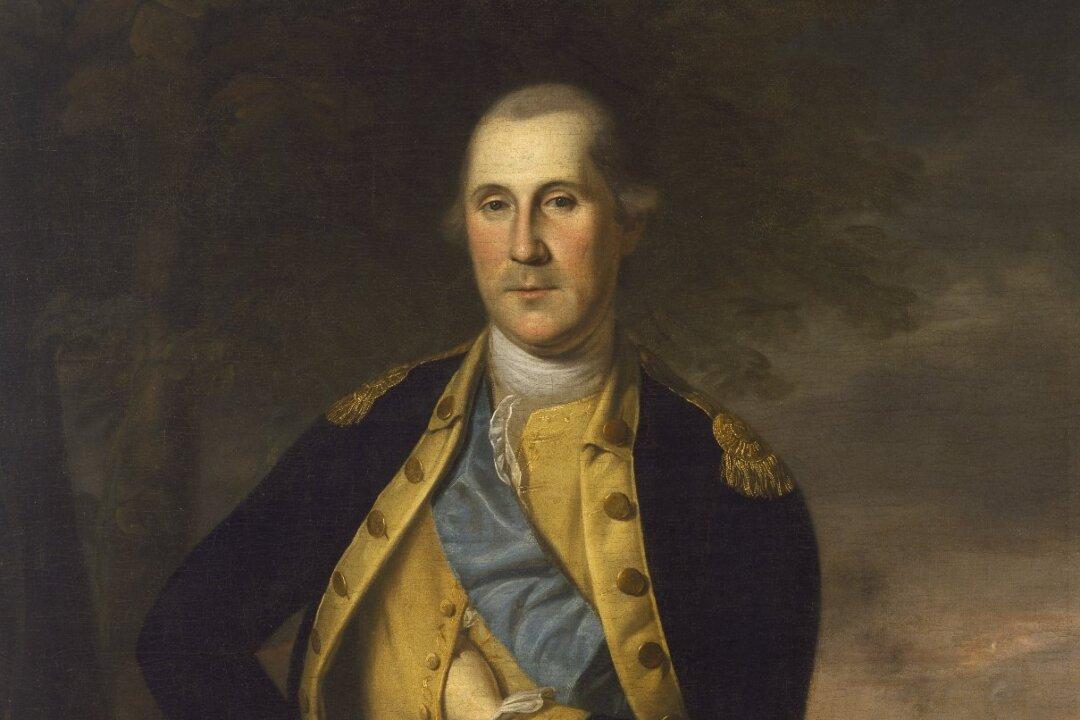

The morning of Dec. 26, 1776, did not start according to plan. The night before, George Washington had led 2,400 Continental Army soldiers across the Delaware River, thinking that two additional troop columns were doing the same at other designated crossing points. The Patriots were tasked with neutralizing a garrison of Hessian auxiliaries at Trenton, New Jersey, before pivoting to nearby British outposts.