Commentary

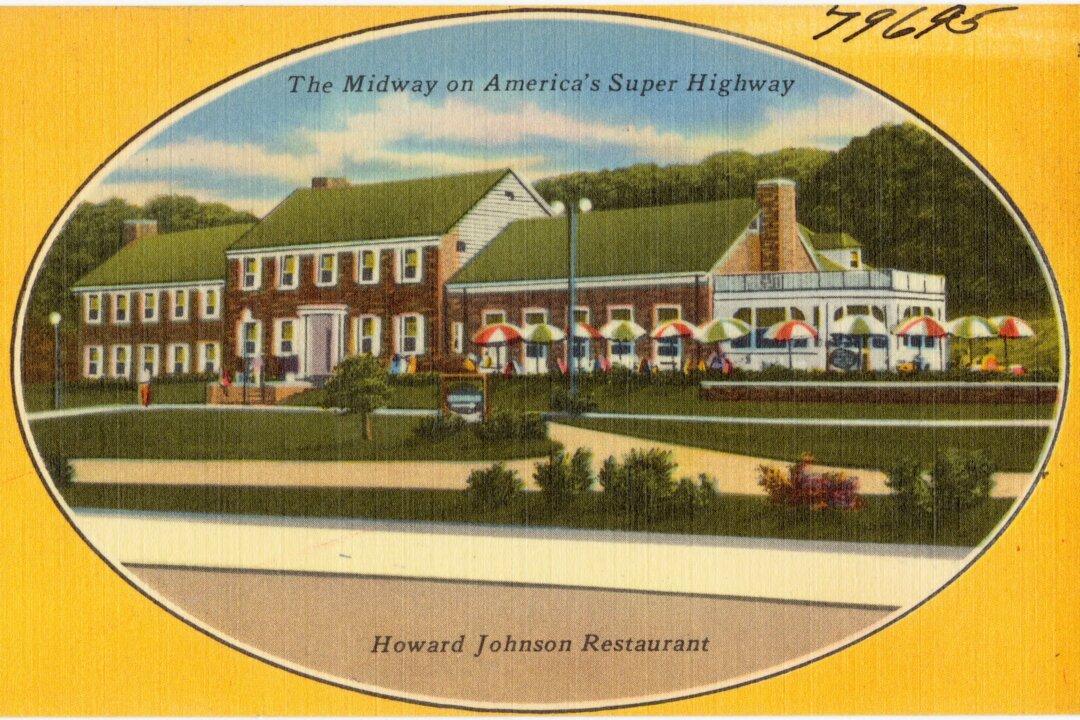

HOLLIDAYSBURG, Pa.—In truth, the last Howard Johnson’s restaurant closed long before the one in Lake George, New York, did last week.

HOLLIDAYSBURG, Pa.—In truth, the last Howard Johnson’s restaurant closed long before the one in Lake George, New York, did last week.