Commentary

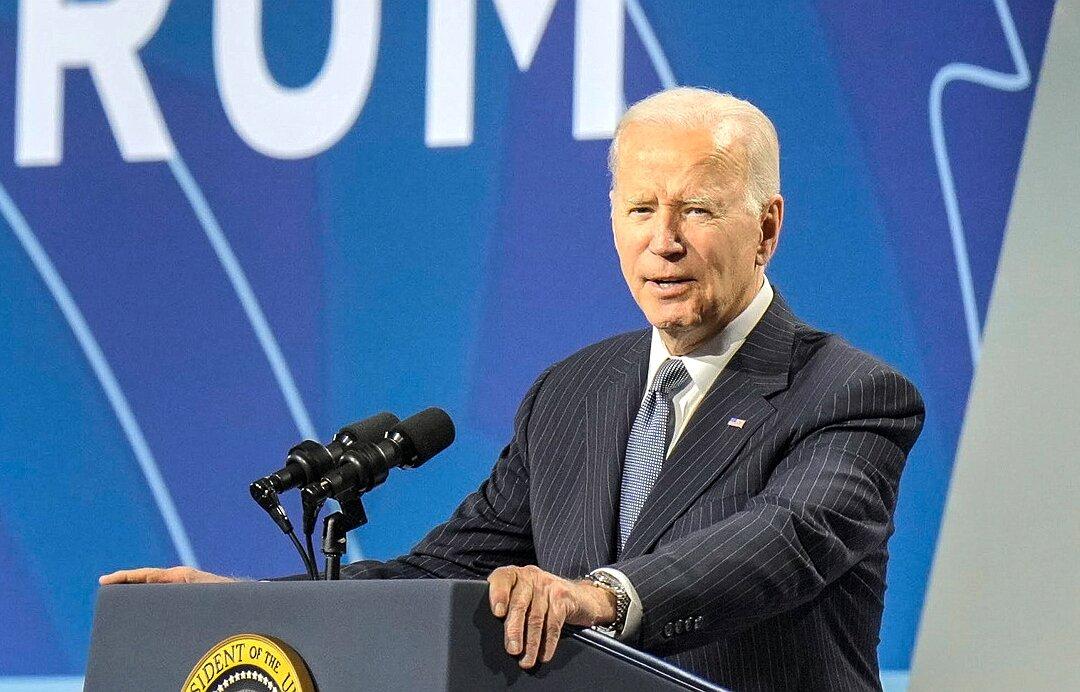

Just a few hours before President Biden tied his political fate to the economy, embracing the term “Bidenomics” in a Chicago speech Wednesday, June 28, he was still trying to dispel worries about a looming recession. A reporter asked Biden, before he boarded Marine One, whether he believed the worst of inflation was over.