Commentary

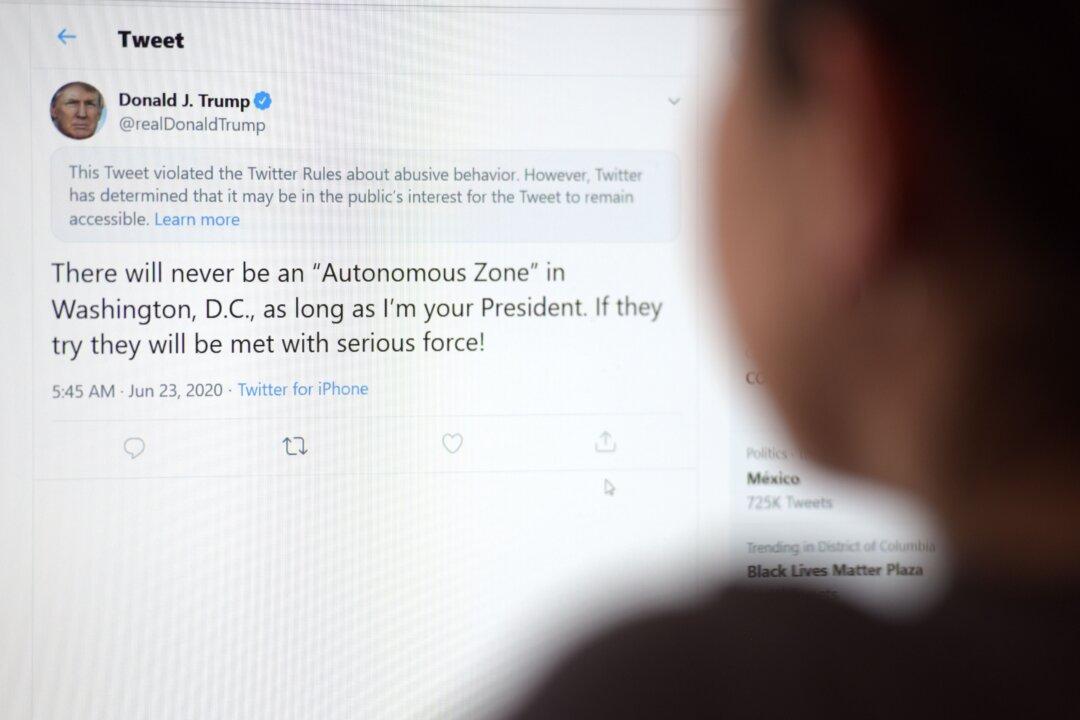

This is the first in a three part series explaining legal and constitutional issues in former President Donald Trump’s lawsuit against Twitter. This installment focuses on how social media censorship abuses federal law.

This is the first in a three part series explaining legal and constitutional issues in former President Donald Trump’s lawsuit against Twitter. This installment focuses on how social media censorship abuses federal law.