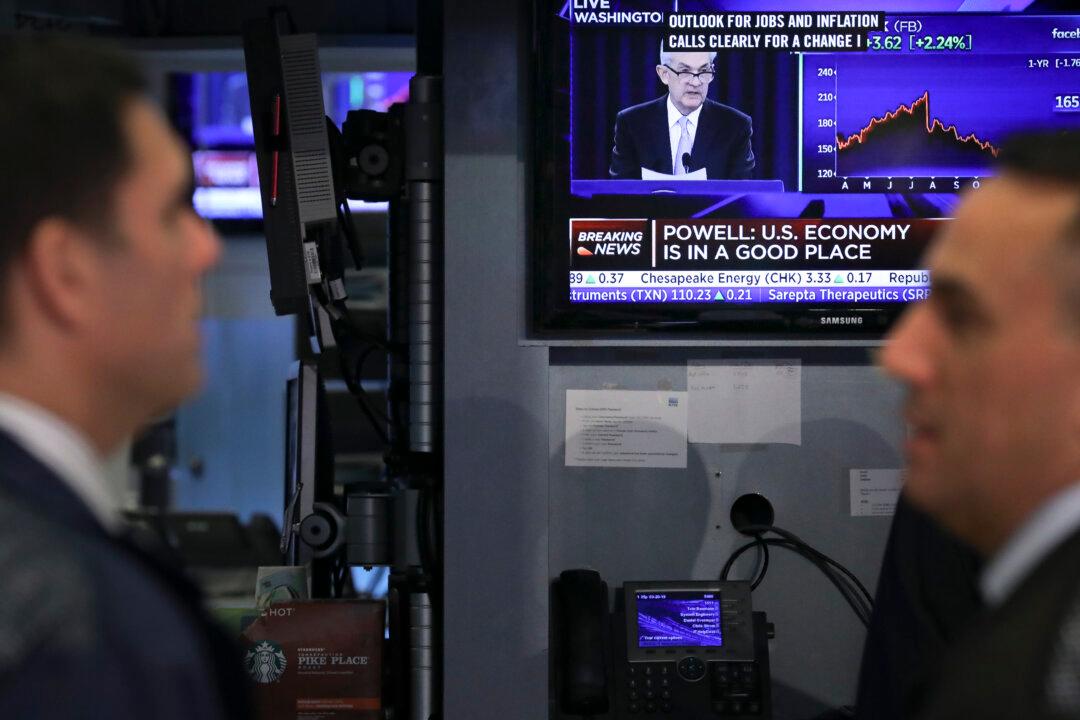

Through his recent appointments, President Donald Trump has begun a much-needed conversation at and about the Federal Reserve. Fundamentally, the president is asking: Does the current Fed truly believe growth causes inflation?

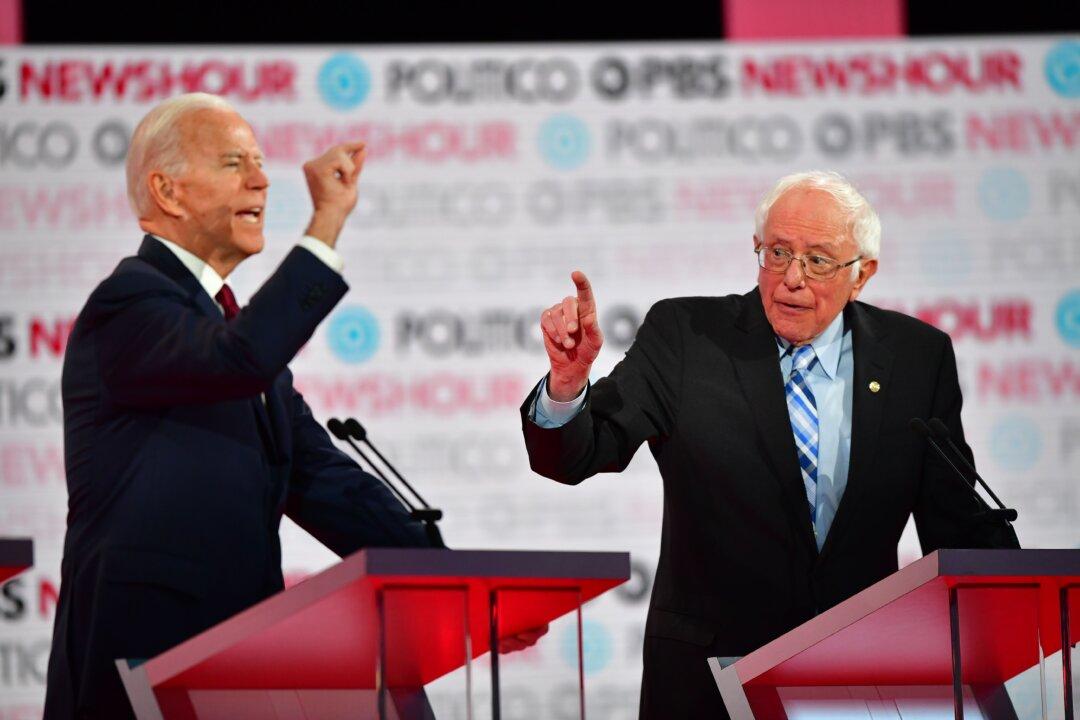

Recently, I made the case that Trump’s desire to fill a Federal Reserve board seat was a potential glasnost moment for the Fed Board. Stephen Moore’s appointment would invite an open discussion on monetary policy. Who can possibly be against open discussions and diversity of opinion?