For centuries there was no question of trade being for “mutual benefit.” It was conducted under a “Beggar thy neighbor” philosophy with national wealth focused on accumulating gold and precious metals.

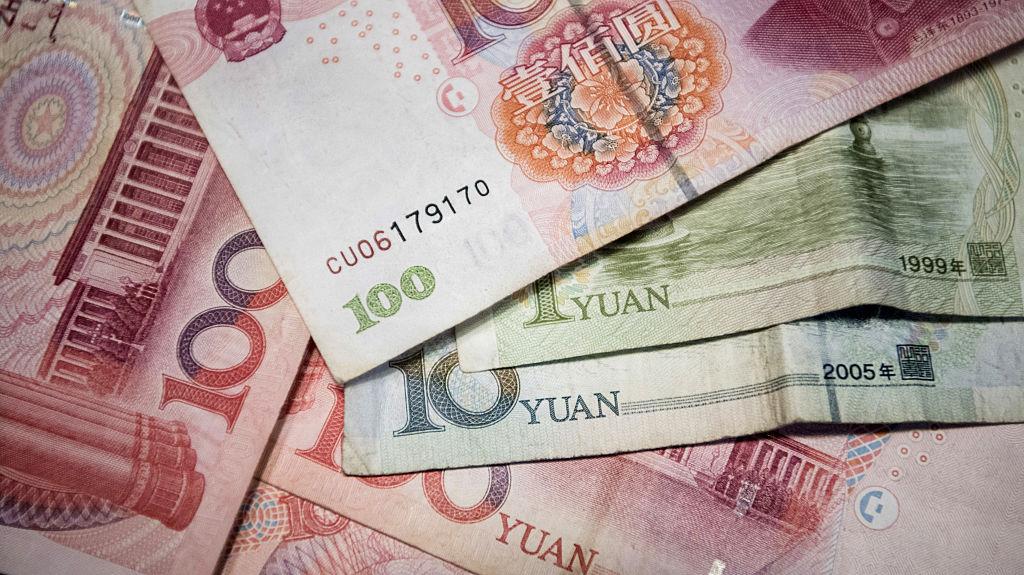

States sought colonies essentially for exploitation: extract useful material from them at low/no price and dump excess industrial products manufactured in the “mother country” at high cost. Such attitudes could result in unpleasant circumstances such as when Great Britain decided that paying for tea with silver was too costly and pushed opium on China. Even feeble Manchu rulers found this exchange invidious, but in two opium wars, Great Britain forced Chinese acceptance. The British image in China is forever tarred.