Commentary

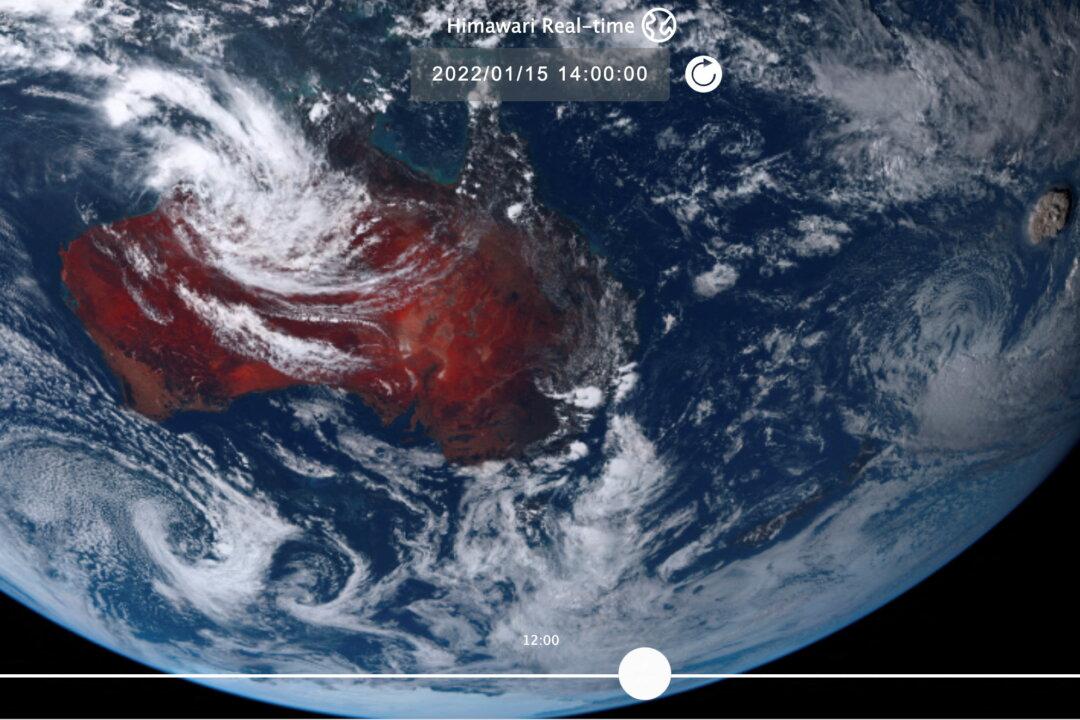

Sometimes you get more than one chance to make a first impression. So it is with the United States and Tonga—the small but important nation in the South Pacific that recently was hit by a volcanic eruption and tsunami.

Sometimes you get more than one chance to make a first impression. So it is with the United States and Tonga—the small but important nation in the South Pacific that recently was hit by a volcanic eruption and tsunami.