Commentary

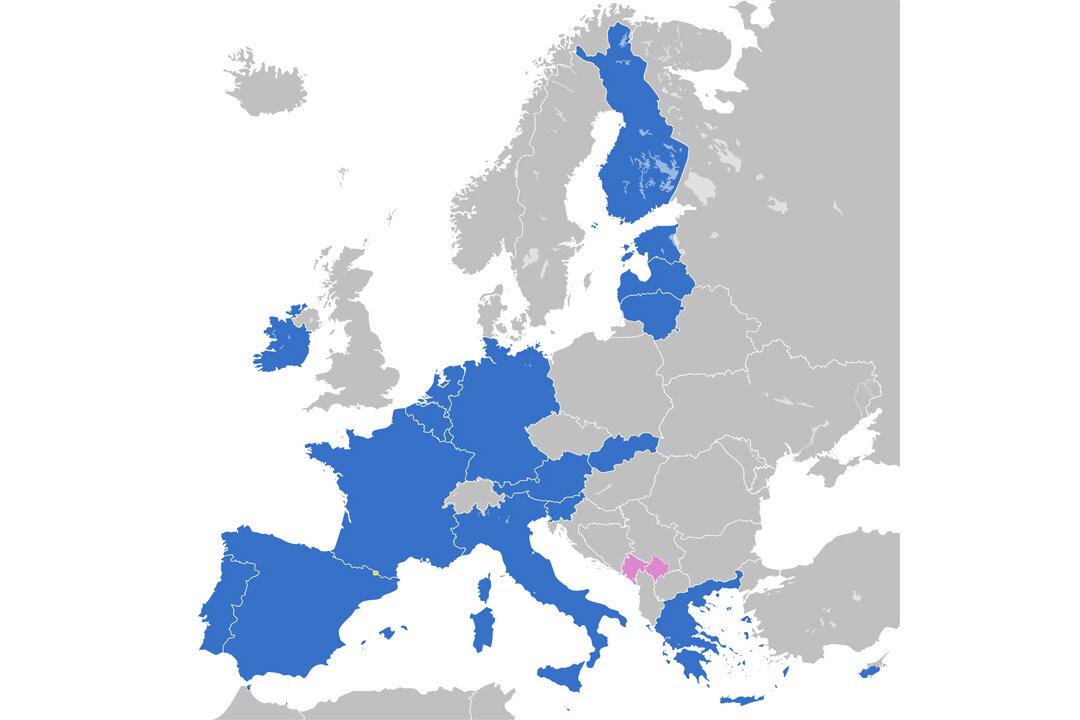

The eurozone economy is expected to collapse in 2020. In countries such as Spain and Italy, the decline, more than 9 percent, will likely be much larger than emerging market economies. However, the key is to understand how and when the eurozone economies will recover.