Commentary

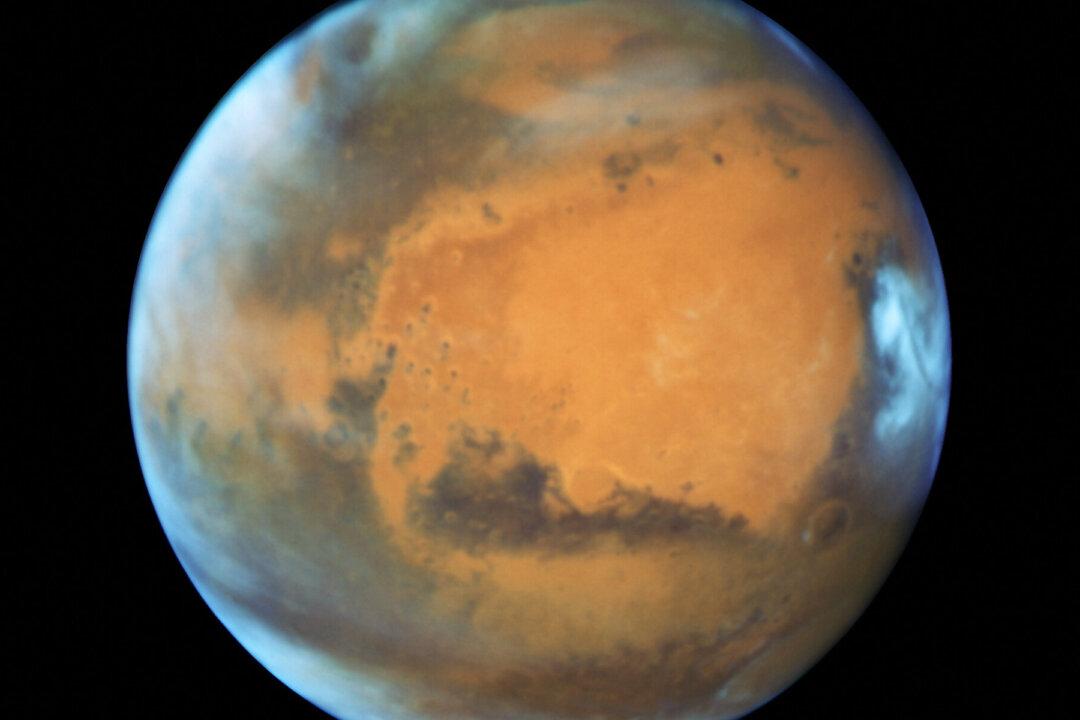

In October, Elon Musk boldly declared that SpaceX, one of six companies he owns, could land a spacecraft on Mars within the next three to four years.

In October, Elon Musk boldly declared that SpaceX, one of six companies he owns, could land a spacecraft on Mars within the next three to four years.