Commentary

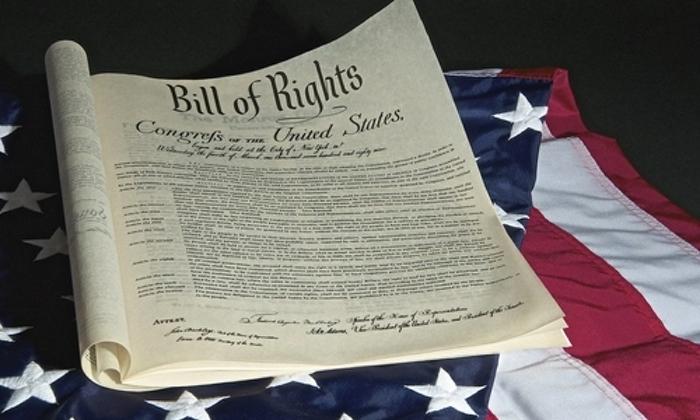

December 15th marks Bill of Rights Day, which commemorates the 232nd anniversary when the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution were ratified. December 15th should be a day all Americans reflect on the unique blessings the Bill of Rights safeguards—the freedom of speech, the right to bear arms, and being protected from undue searches and seizures, to name just a few.