Commentary

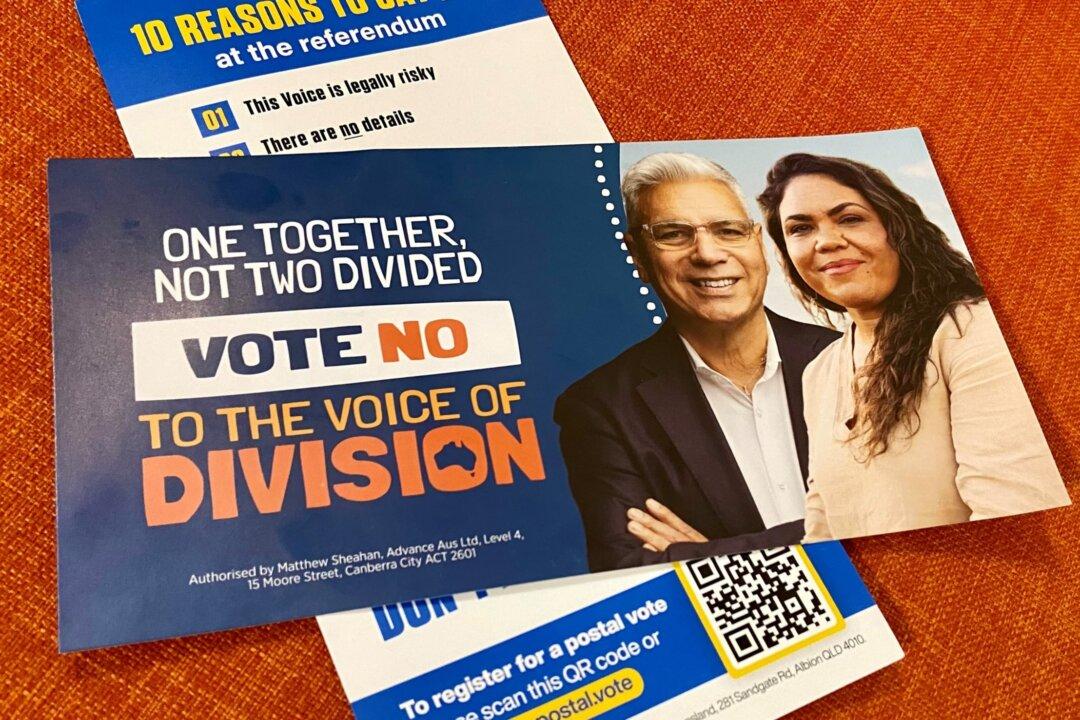

In a historic national vote in mid-October, Australians decisively rejected a constitutional amendment that would have permanently enshrined race-based rights and privileges. The referendum question asked whether the Constitution should be amended to recognize aboriginals as the “first peoples” of the country and then authorize creation of a permanent indigenous group—the Voice—to advise both Parliament and the executive government (Cabinet).