Commentary

The U.S.–China tech war is complicated and heating up.

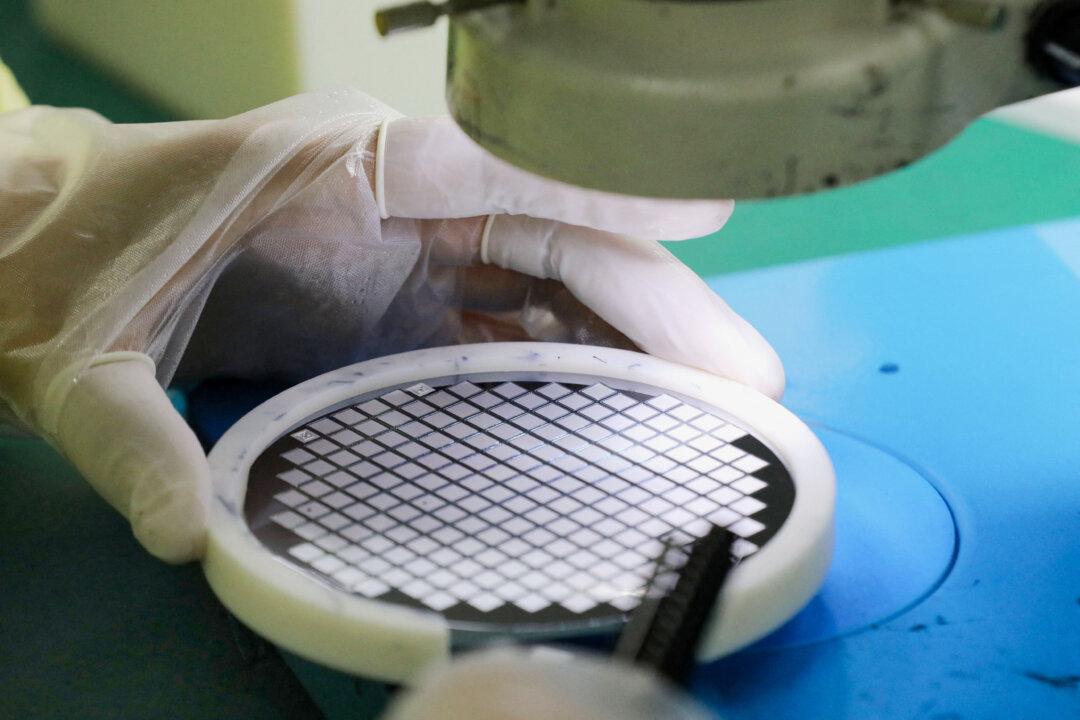

First, Washington is continuing to apply pressure on Beijing where it counts—by blocking its access to the most advanced global semiconductor technologies. Beijing is responding by trying to control rare minerals used in tech processes. The minerals and semiconductors that each attempts to deny the other are critical for military production.