Commentary

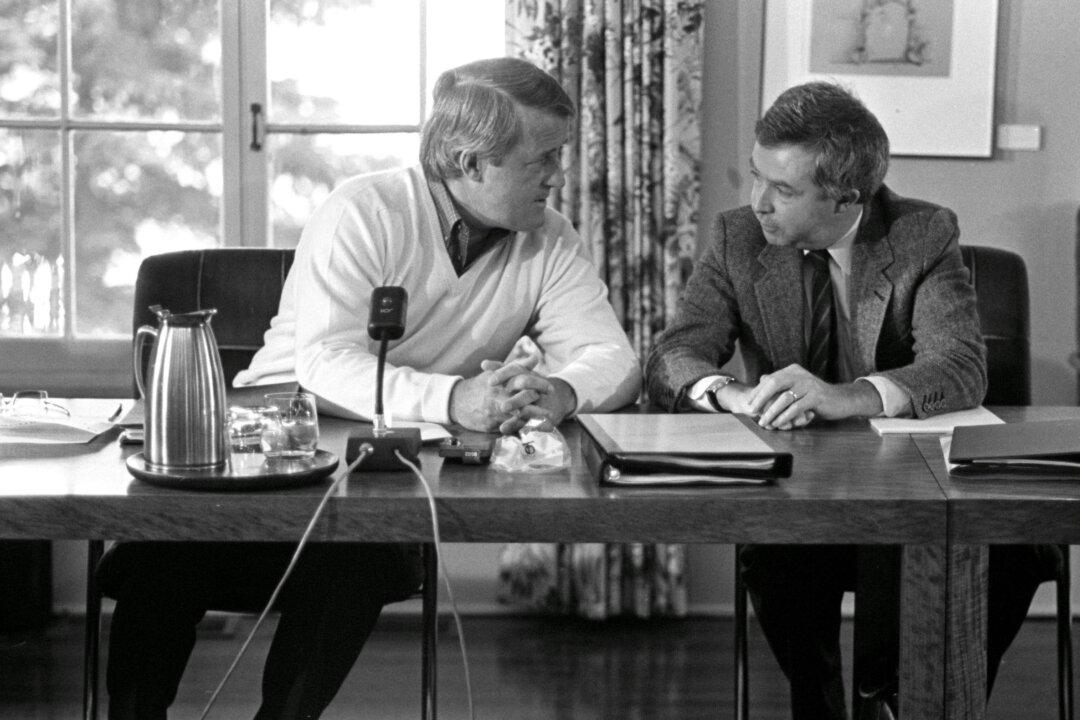

The death of Brian Mulroney, the 18th Prime Minister of Canada, will remind Canadians of many things—his evisceration of John Turner in a televised debate (“you had an option, sir!”), his gigantic 1984 electoral victory, the introduction of the GST, the negotiation of a free trade pact with the United States, and his work to muster international support against South African apartheid.