Commentary

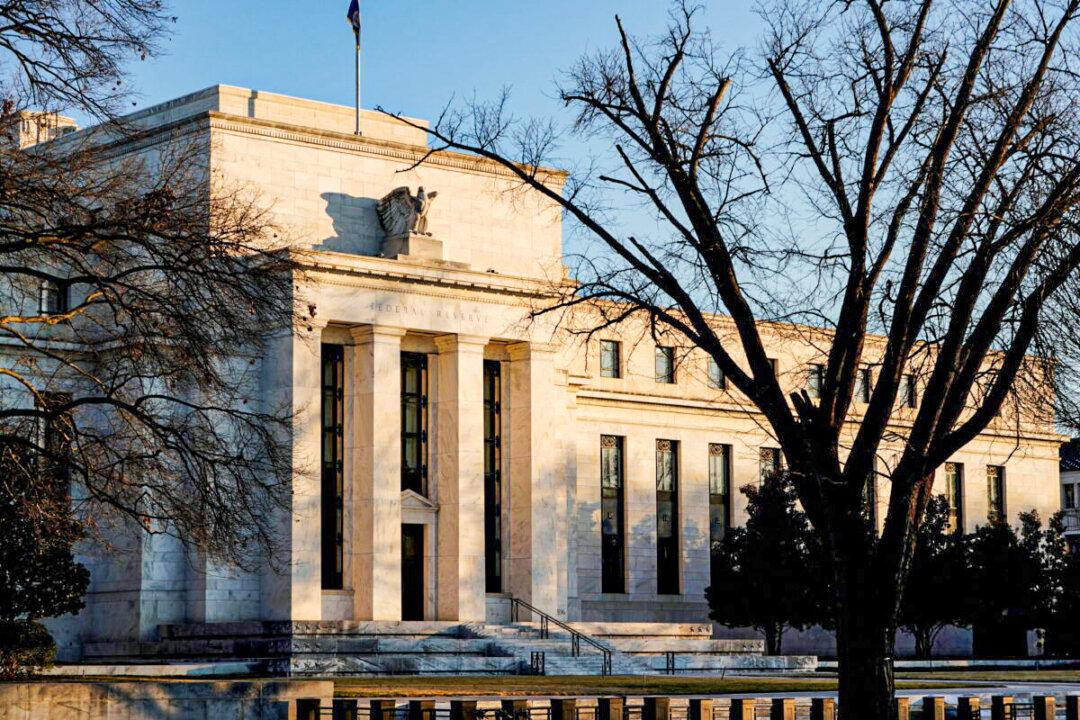

On Nov. 3, the Federal Open Market Committee indicated the economy had met the committee’s targets to begin reducing the pace of its U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed security purchases by $15 billion per month. While history has shown that Treasury yields fall while the Fed is engaged in a balance sheet taper, the market initially reacted by sending Treasury yields higher.