Commentary

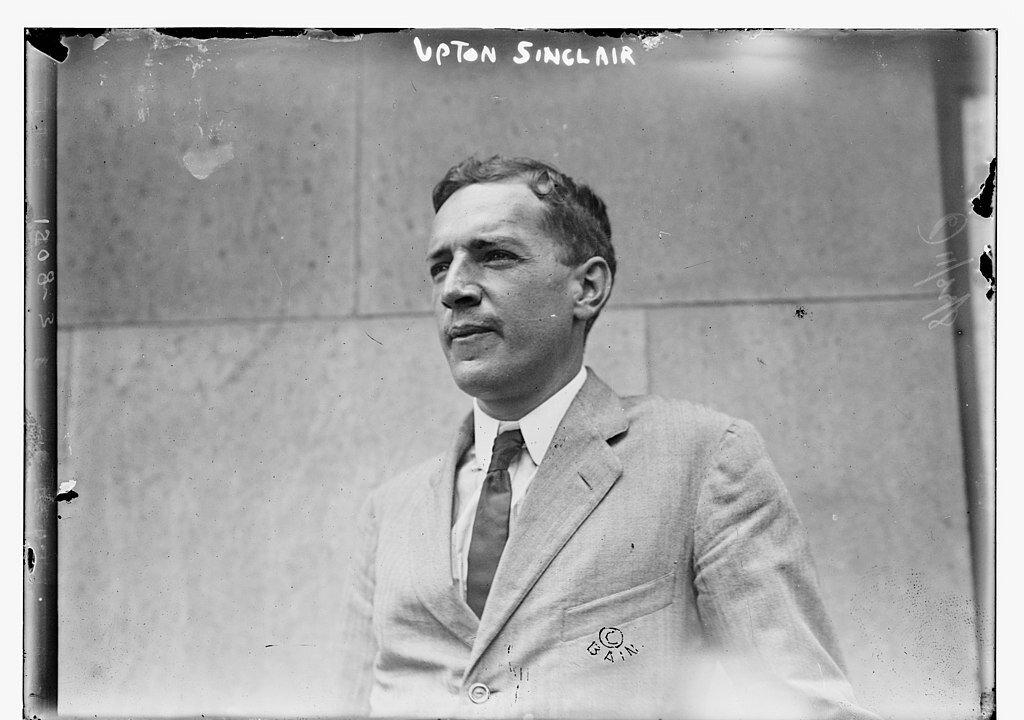

The writer Upton Sinclair may not have invented risk communication in the United States, but he surely provided one of the most important, most faithfully likened models that has been followed, for better or worse, ever since.

The writer Upton Sinclair may not have invented risk communication in the United States, but he surely provided one of the most important, most faithfully likened models that has been followed, for better or worse, ever since.