Commentary

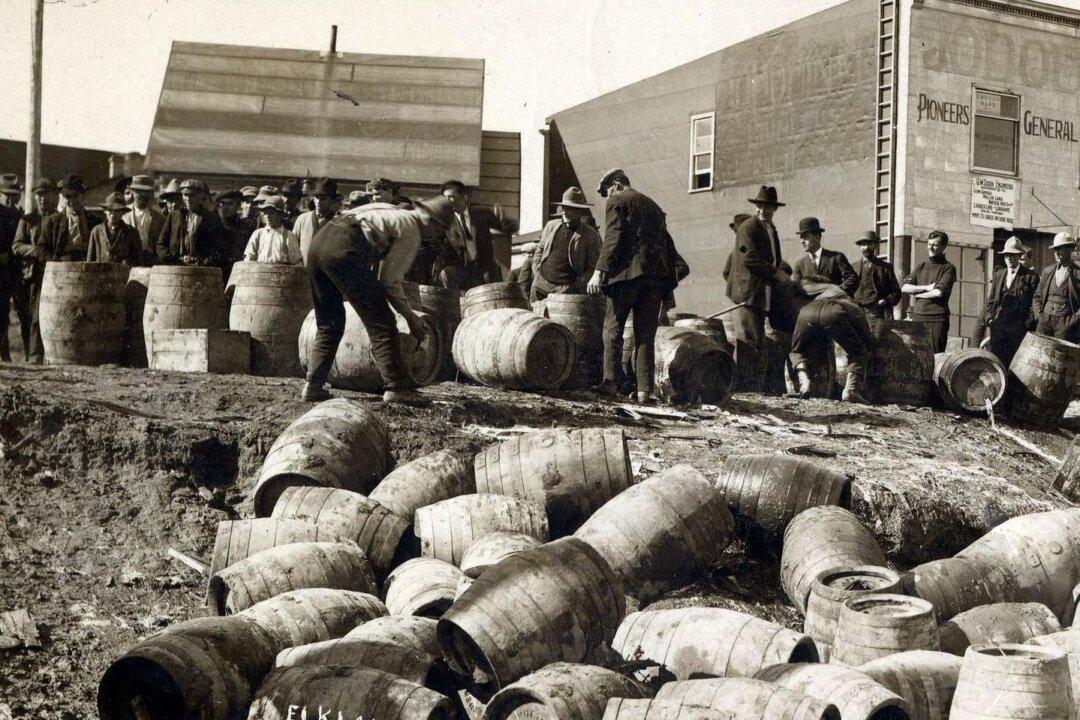

Temperance activists from Victorian times to the interwar years strove to reduce or ban drinking in Canada, with mixed success.

Temperance activists from Victorian times to the interwar years strove to reduce or ban drinking in Canada, with mixed success.