At the beginning of the 19th century, the celebration of Christmas in the English-speaking world was in a state of disrepute. Observing the festival had been banned by Puritan governments in Scotland, England, and the New England colonies, and even when it became legal again to mark the holiday, Christmas had become associated with the lower orders of society. Stripped of its religious significance by Calvinist Protestants and Enlightenment freethinkers, Christmas had come to be associated with drunkenness and disorder—noise in the streets, overindulgence in food and drink, and riotous behaviour directed against the middle class.

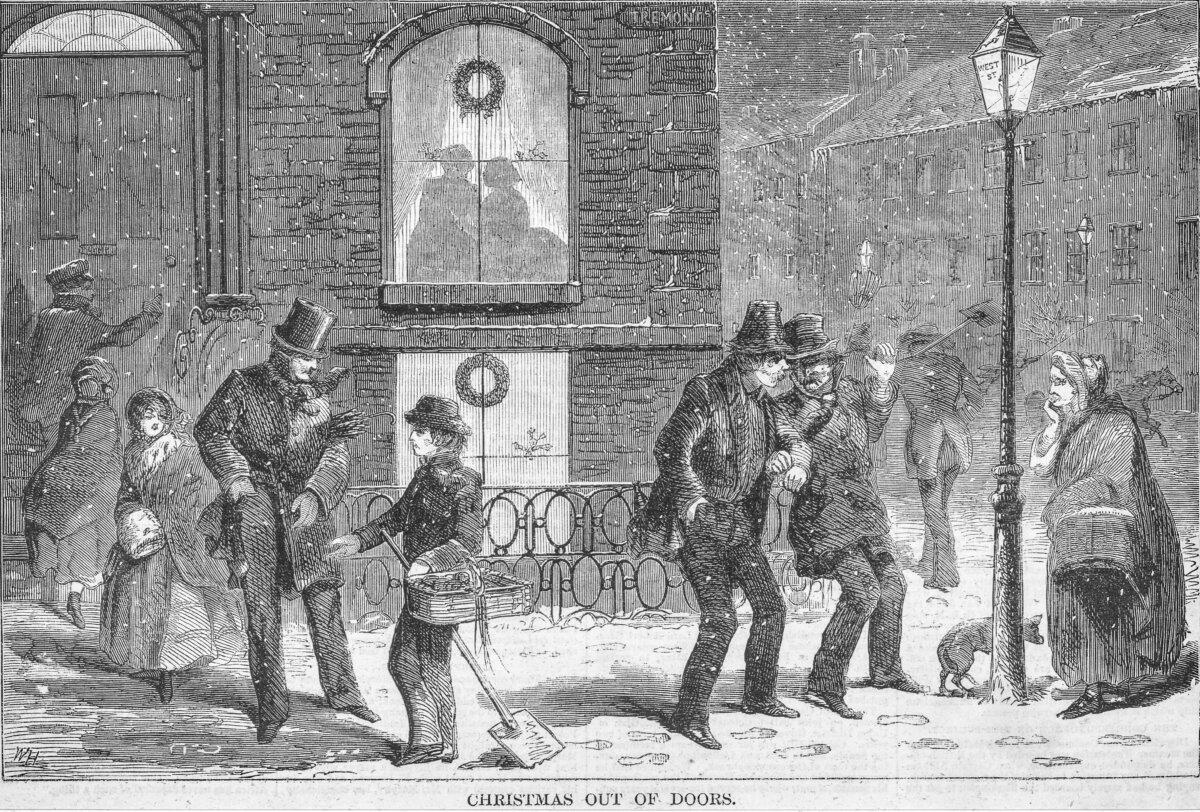

Engraving of the illustration “Christmas out of doors” by American artist Winslow Homer, showing the harshness of a cold snowy winter on the streets, printed in Harper's Weekly in New York in December 1858. Archive Photos/Getty Images