Commentary

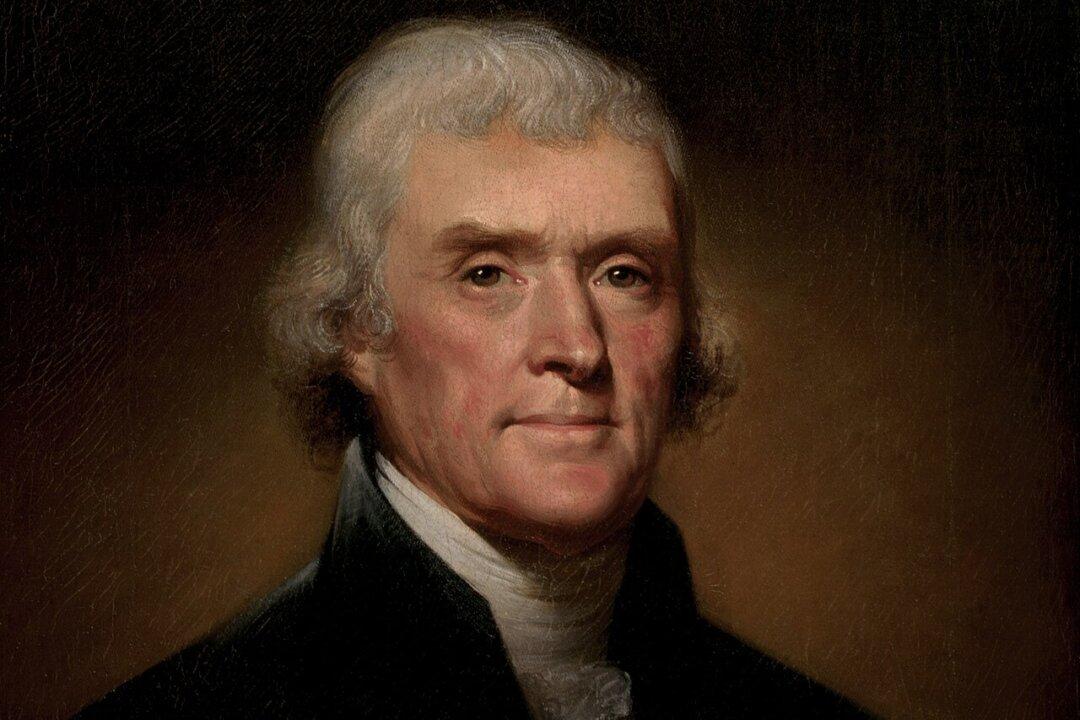

Thomas Jefferson won the presidency in 1800 in an upset election over incumbent John Adams that upended the financial and political establishment. He immediately repealed the Alien and Sedition Acts that stood in violation of the First Amendment and embarked on a political journey to entrench the Jeffersonian vision of limited government and freedom for all.