Commentary

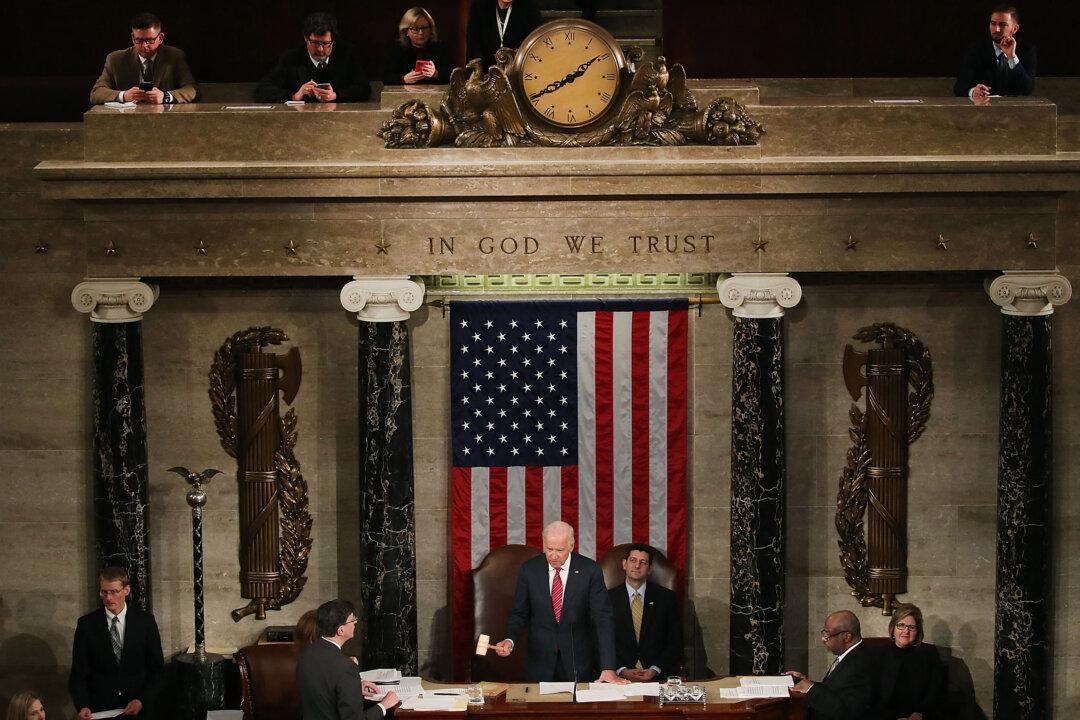

I recently had the chance to talk with a group of high school students who asked me questions about the Electoral College.

I recently had the chance to talk with a group of high school students who asked me questions about the Electoral College.