Commentary

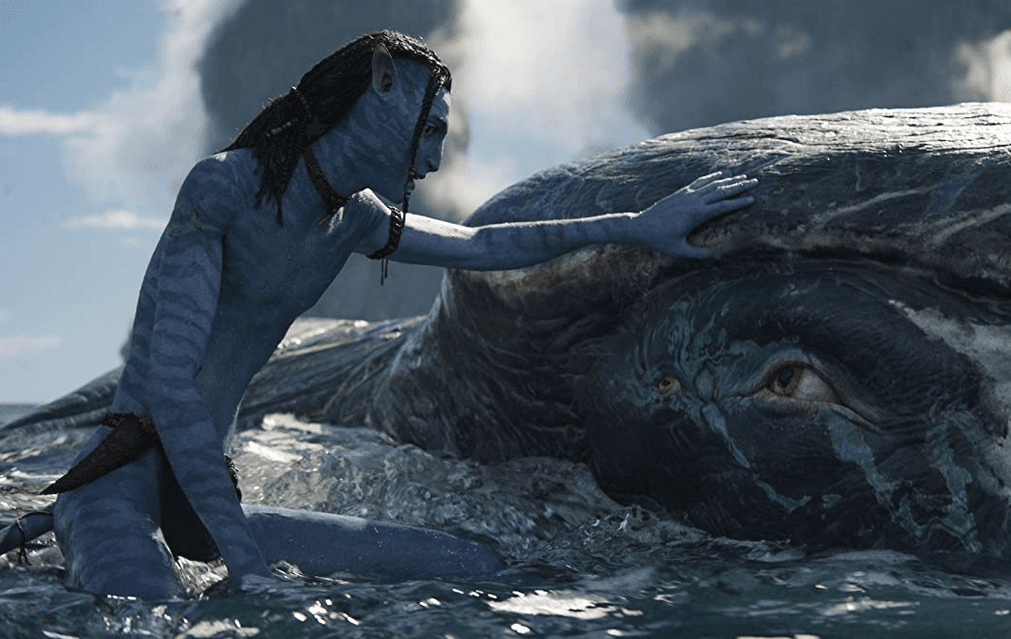

After 13 years of waiting, “Avatar“ finally has a sequel in the newly released “Avatar: The Way of Water.” The movie has stunning visuals, a decent story, and has received mostly positive reviews. It also grossed a whopping $2.024 billion worldwide, making it the sixth highest-grossing film of all time.