Commentary

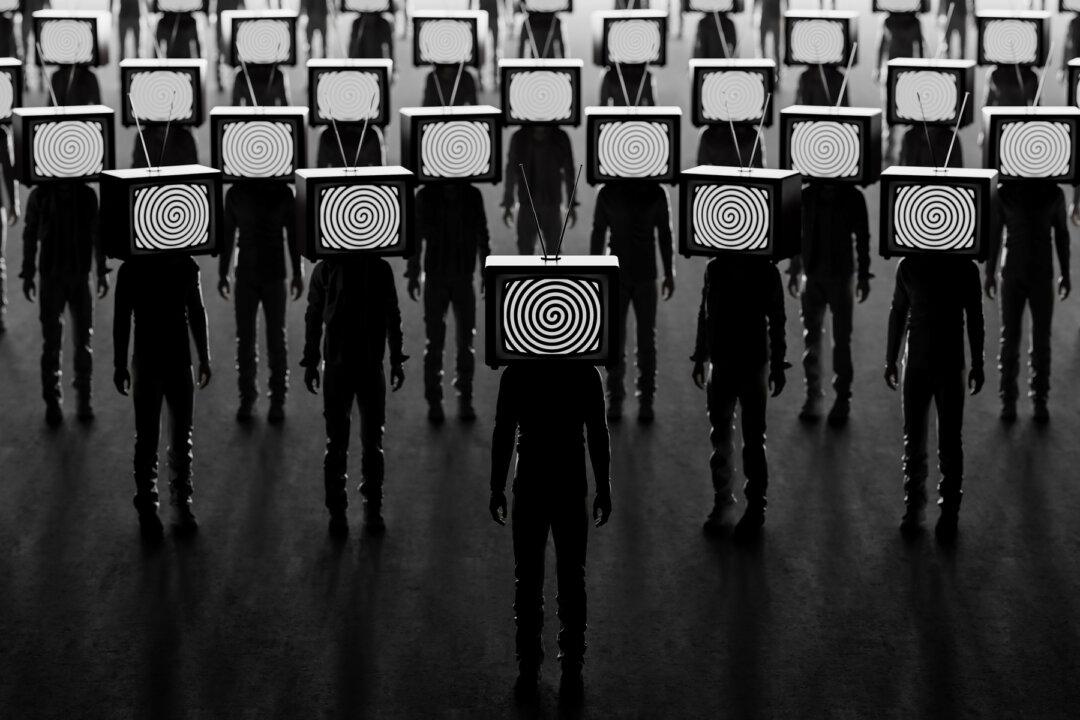

More and more people in the United States will be wising up to their government’s use of behavioural science—or ‘nudging’—as a means of increasing compliance with Covid-19 restrictions. These psychological techniques exploit the fact that human beings are almost always on ‘automatic pilot,’ habitually making moment-by-moment decisions without rational thought or conscious reflection.