Commentary

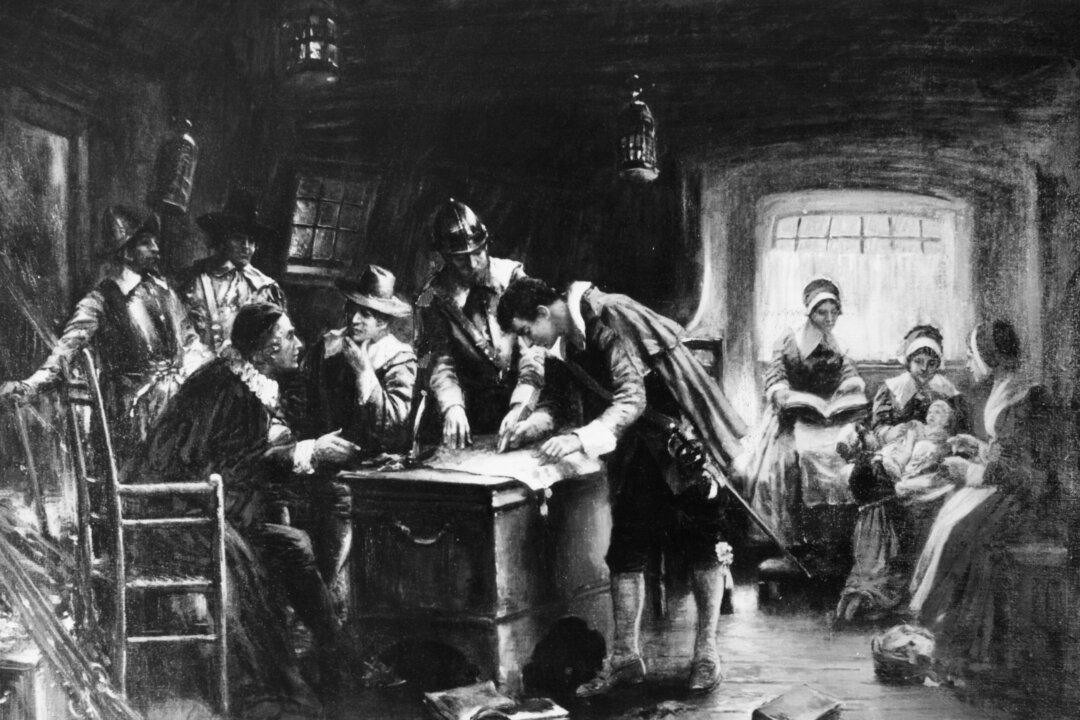

The year 2020 marks the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower Compact. The agreement, signed by 41 Pilgrim Fathers in 1620, was the first in a series of documents memorializing deliberate self-government in America.

The year 2020 marks the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower Compact. The agreement, signed by 41 Pilgrim Fathers in 1620, was the first in a series of documents memorializing deliberate self-government in America.