Commentary

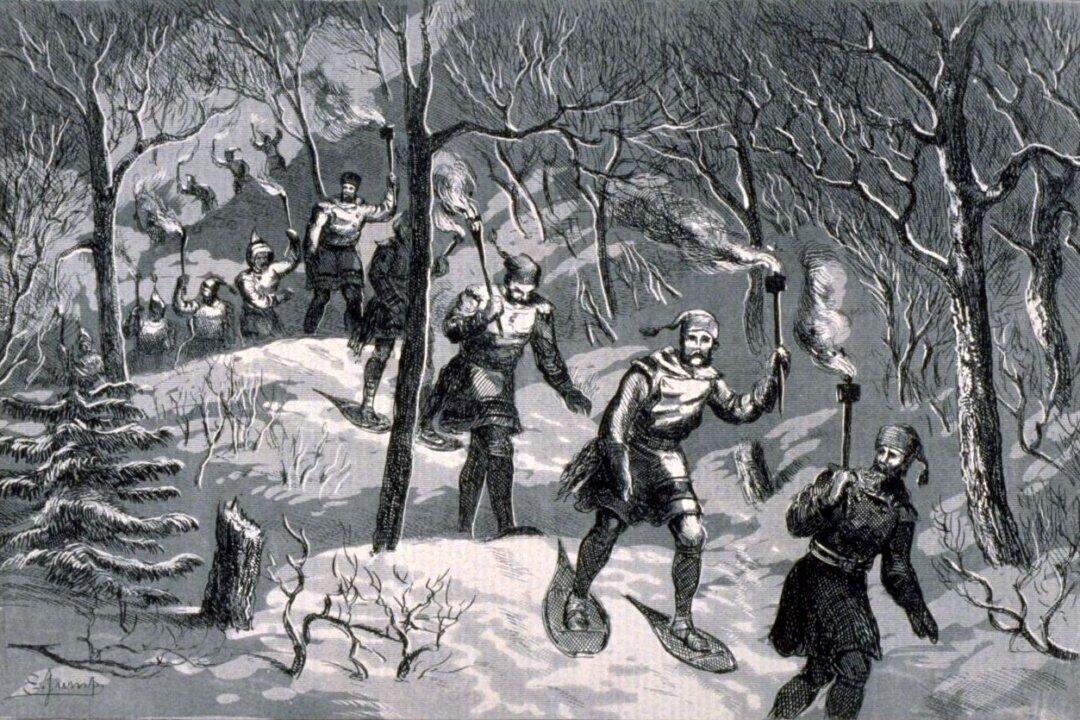

In the 19th century, men of Canada’s greatest city, Montreal, used to test their mental and physical stamina every week during the winter, no matter how severe the weather, by traversing “the mountain,” also known as Mount Royal, on snowshoes.