Commentary

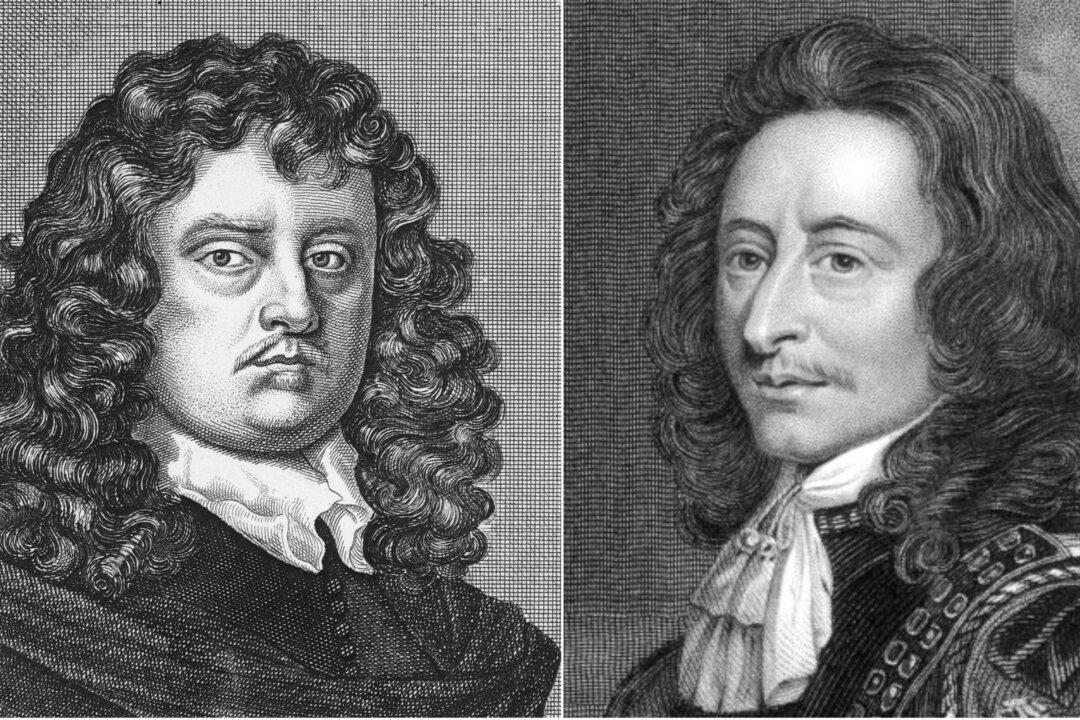

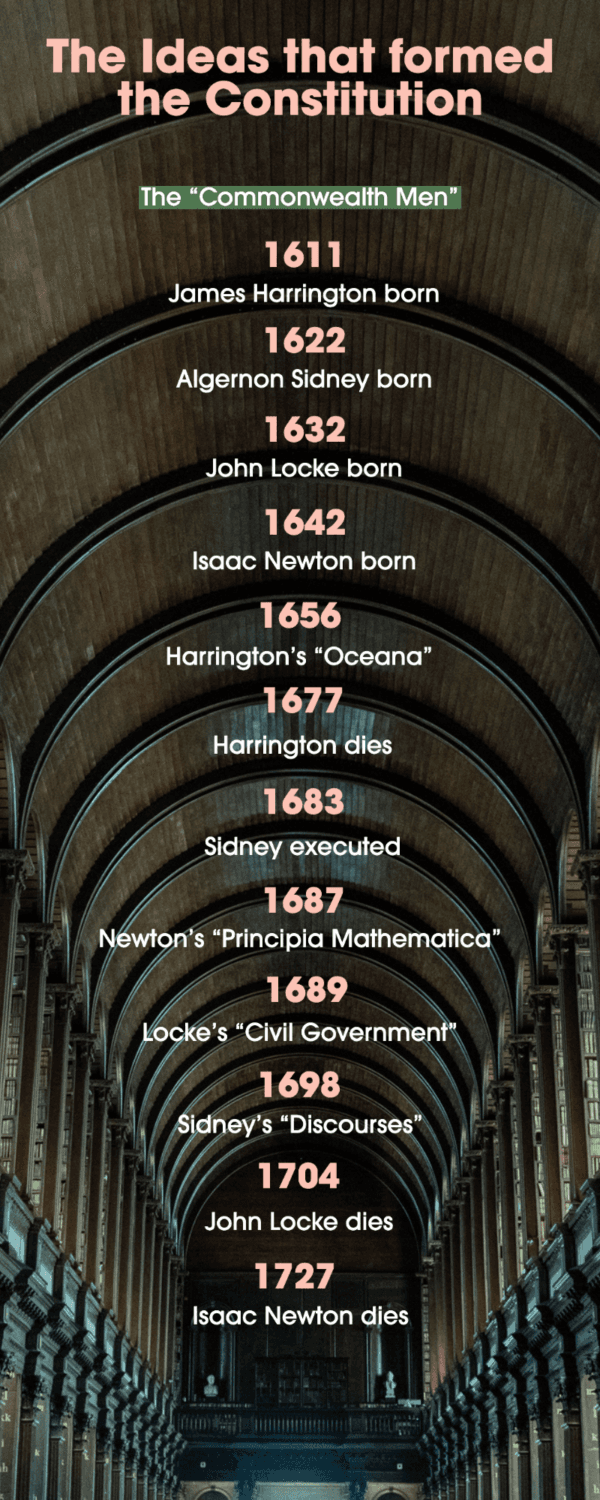

In the 17th century, England, which always had been a monarchy, flirted with republicanism. From 1649 to 1660, England actually was a republic, at least in theory: King Charles I had been executed, and the country became a “protectorate” under Oliver Cromwell. Not long after Cromwell’s death, however, a “Convention Parliament” invited the deceased king’s son, Charles II, to take the throne, and England’s experiment in republicanism was over.

In the 17th century, England, which always had been a monarchy, flirted with republicanism. From 1649 to 1660, England actually was a republic, at least in theory: King Charles I had been executed, and the country became a “protectorate” under Oliver Cromwell. Not long after Cromwell’s death, however, a “Convention Parliament” invited the deceased king’s son, Charles II, to take the throne, and England’s experiment in republicanism was over.