Commentary

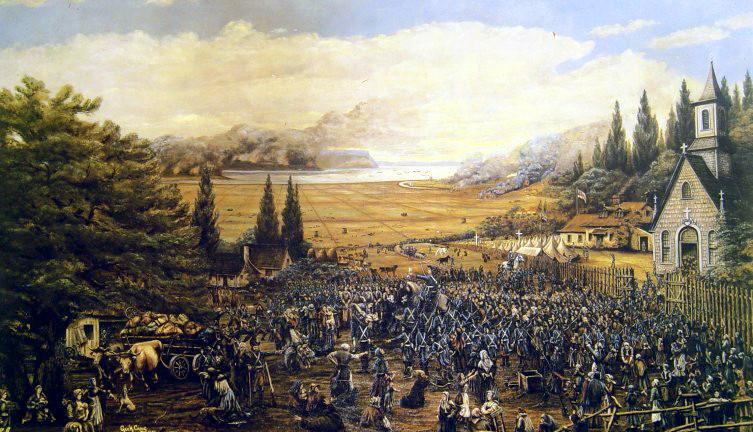

Starting in the 11th century, the kings of England and the kings of France engaged in a series of seemingly interminable wars. They were fought at first in Europe, but as both nations acquired global empires, these conflicts spread to their colonial possessions around the world. Territories in what is now Canada naturally were caught up in these struggles.