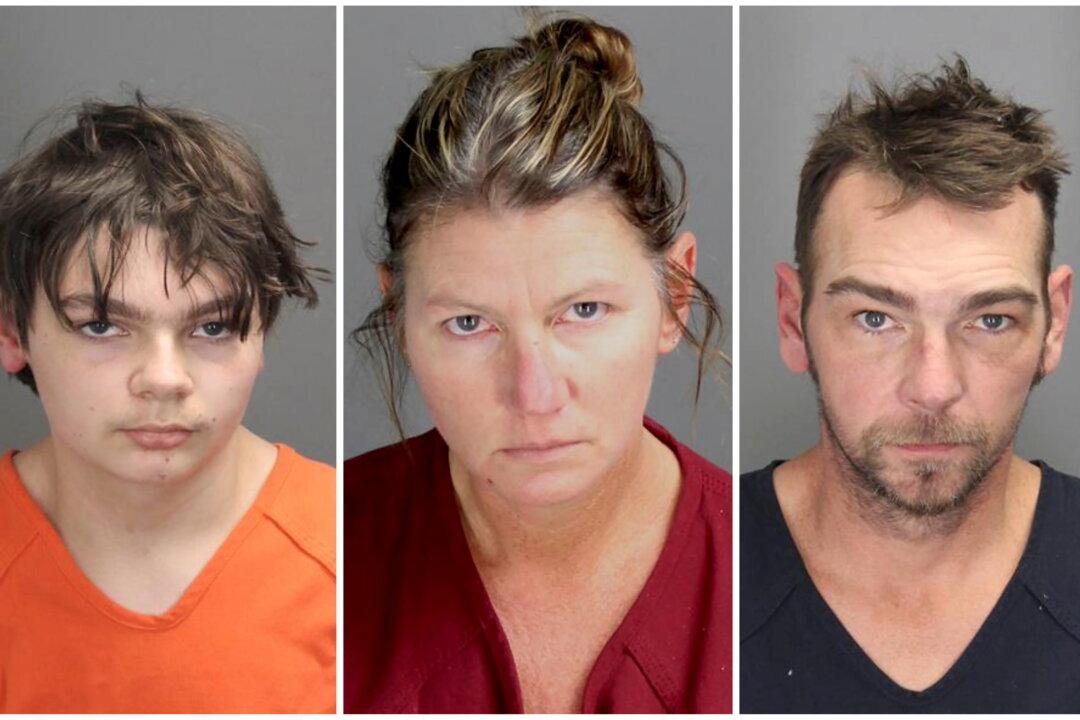

Commentary

Nearly every state has a citizen’s arrest law allowing civilians to detain someone if they have witnessed a crime being committed. Some of these laws allow only felony suspects to be held until law enforcement arrives, while others also allow those suspected of “breach of peace” misdemeanors to be held.