Commentary

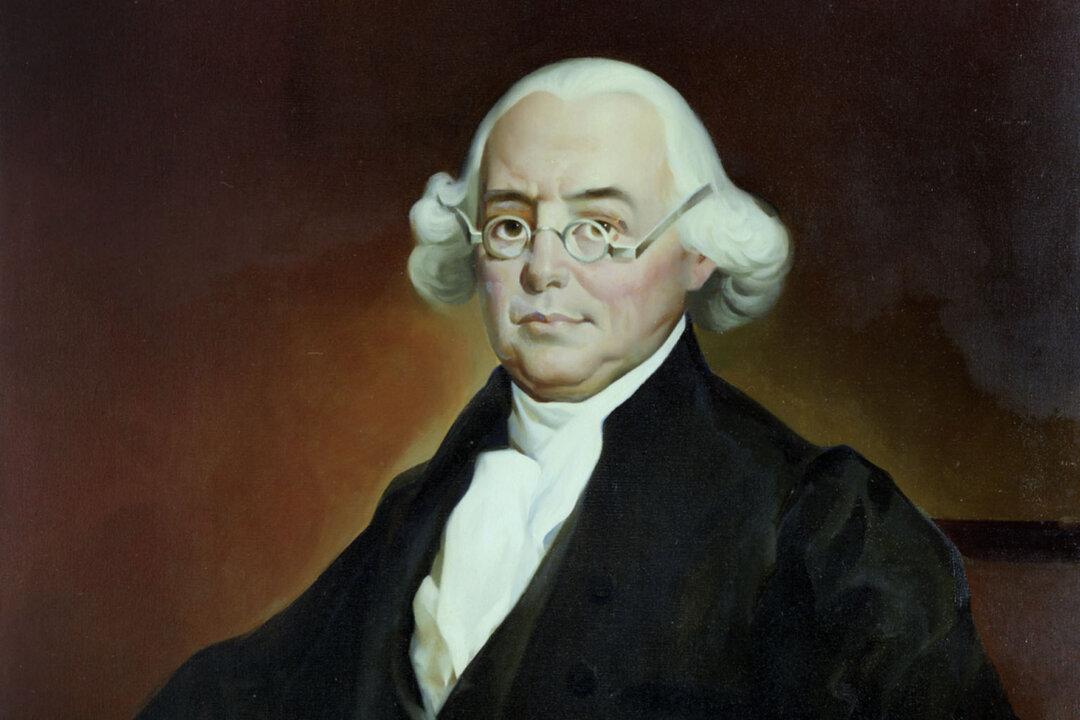

James Madison was the individual with the most influence on the framing (writing) of the Constitution. Some authors rate James Wilson second.

James Madison was the individual with the most influence on the framing (writing) of the Constitution. Some authors rate James Wilson second.