Commentary

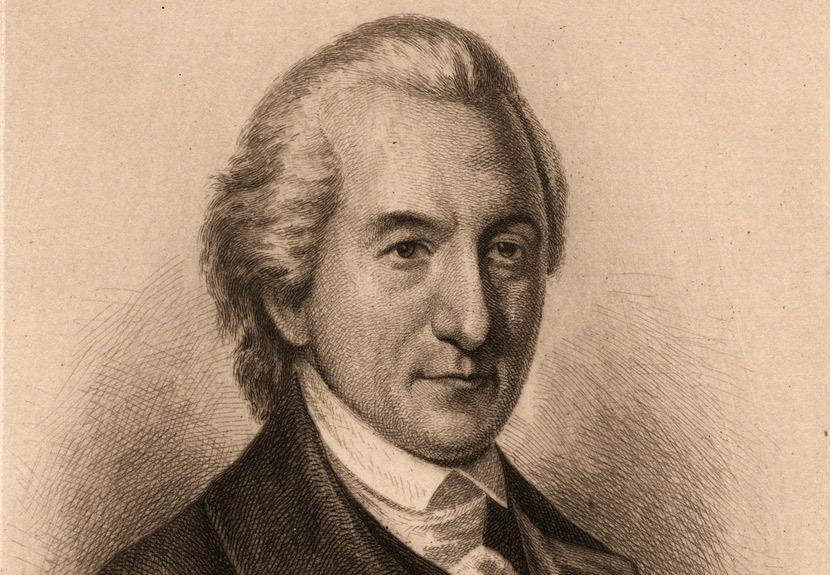

Like James Madison, the subject of the previous essay in this series, John Dickinson was one of those Founders about whom it could be said that “without him, we probably would not have a Constitution.” However, Madison’s contribution is justly renowned, while Dickinson’s has been unfairly overlooked.