Commentary

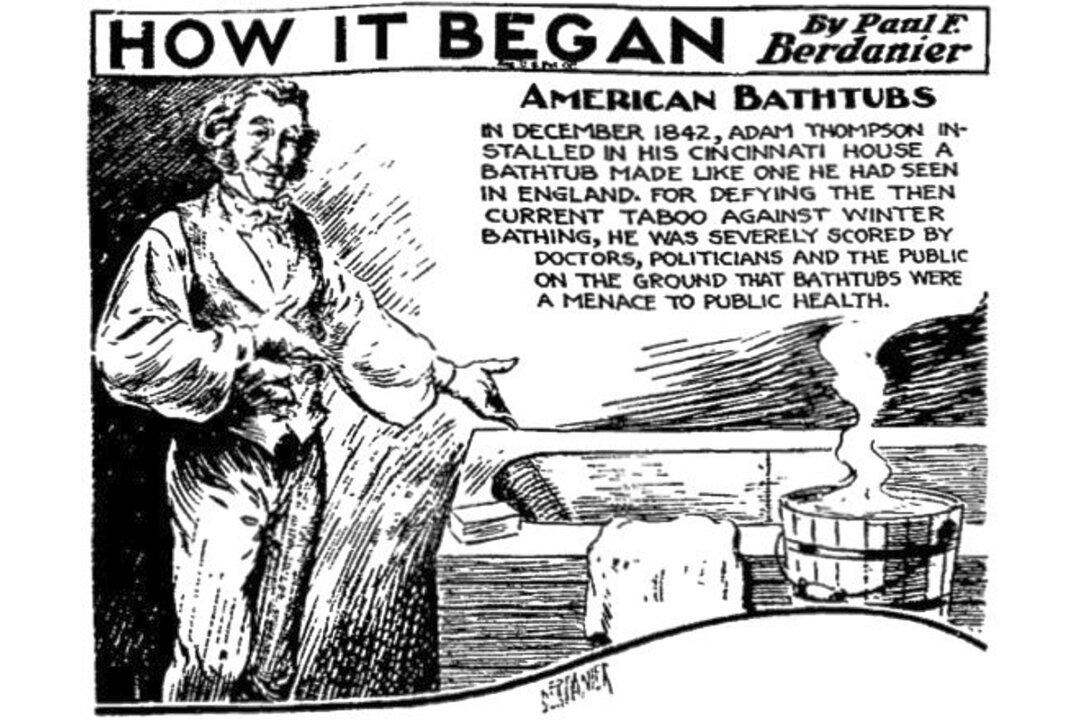

On Dec. 28, 1917, the New York Evening Mail carried a fascinating article on the history of the bathtub in the United States, which seems to have gone through an absorbing series of technological iterations and public controversies concerning good taste. Even the medical community got involved to warn of the bathtub’s threat to personal hygiene.