Commentary

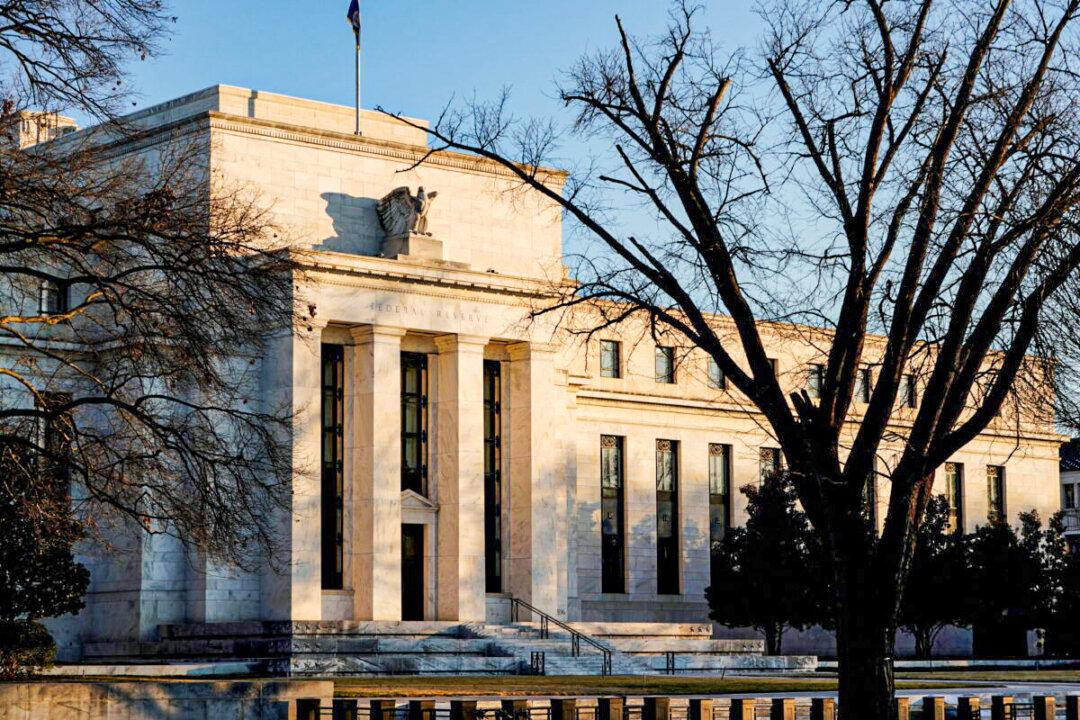

After 29 months of operation, the Federal Reserve will end its large-scale asset purchase program, or quantitative easing, on March 11. While many believe the end of QE is long overdue as it stoked the inflationary fire, others suddenly find themselves facing uncertainty.