Commentary

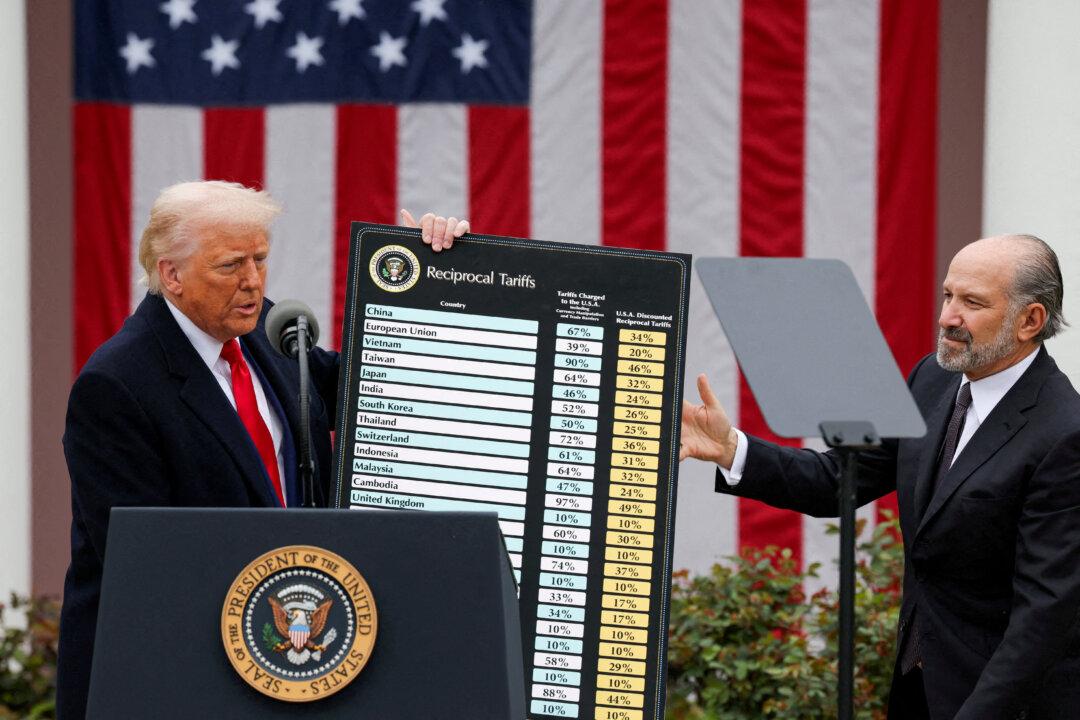

As President Donald Trump announced this week that he was going forward with a more than 100 percent tariff on China and a 10 percent tariff on the rest of the world, pending a 90-day negotiation period, the world and financial markets seemed to breathe a sigh of relief.