Commentary

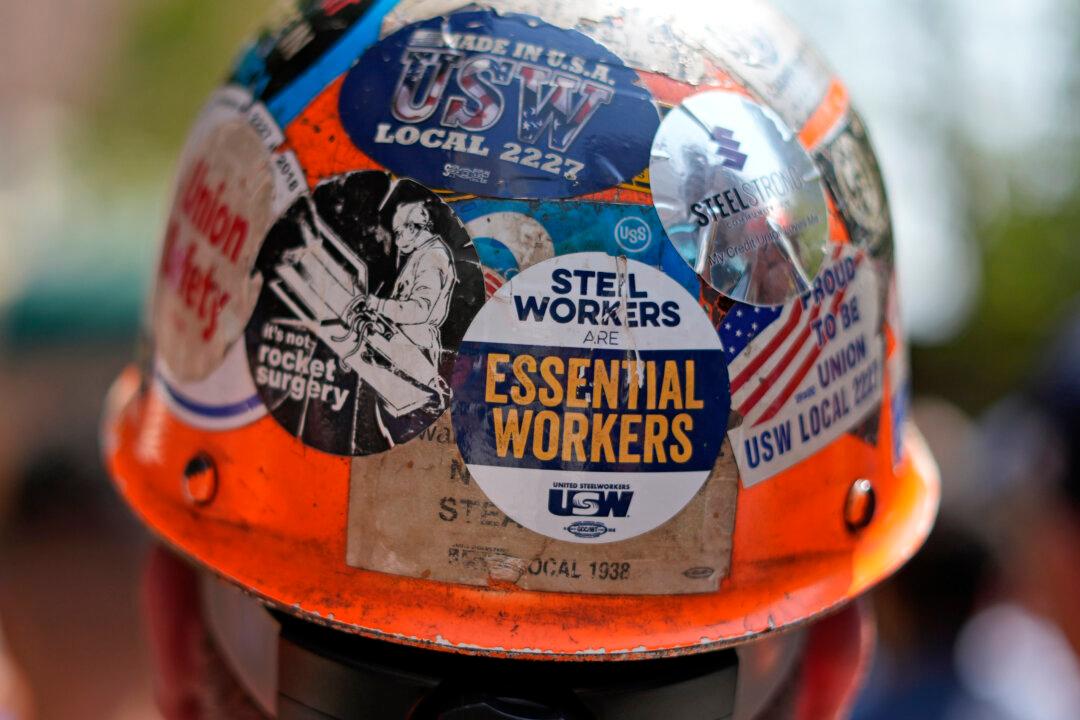

All contenders for the U.S. presidency agree that U.S. Steel as a company should stay under American ownership and should not be sold to Japanese firm Nippon Steel for $14.1 billion. This is despite Nippon’s promise to retain all American jobs at union wages, upgrade all facilities, and generally save the company. Otherwise, U.S. Steel will most likely have to leave Pittsburgh, its home since 1901, and close factories.