Commentary

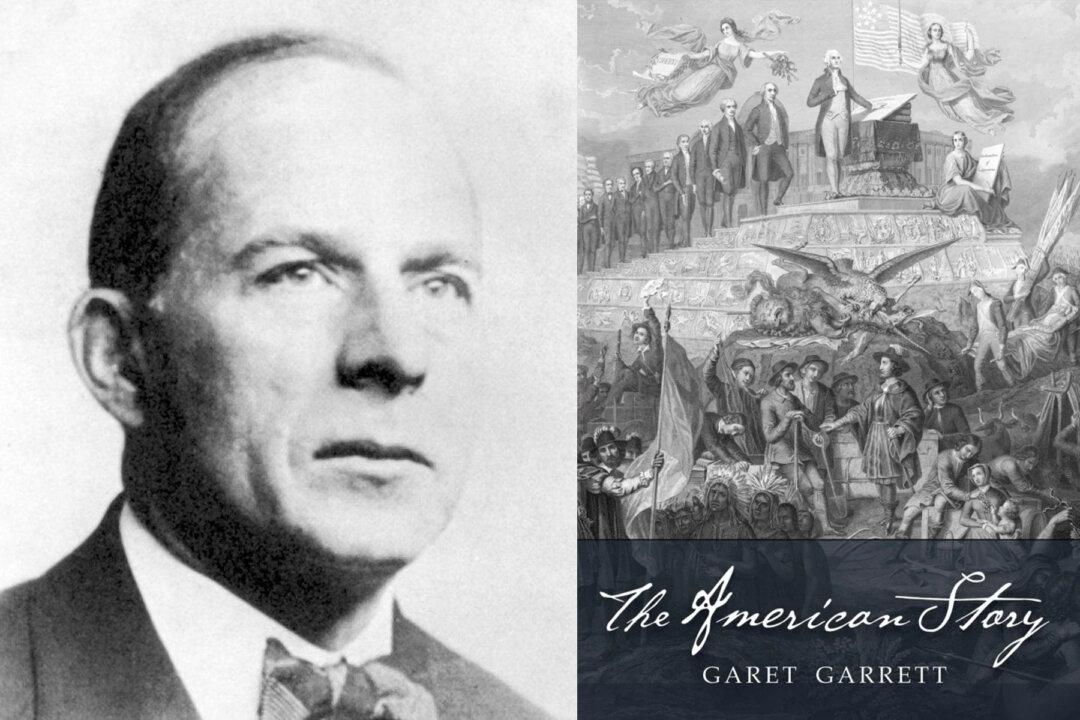

One of the best nonfiction books to appear following the onset of the Great Depression was written by the financial journalist Garet Garrett (1878–1954). It is called “The Bubble that Broke the World” (1931), and it was a bestseller. His analysis was exactly right. This was not a crisis of capitalism, he wrote, but of postwar credit expansions and imbalances. The economic downturn represented the coming due of the bill, and a cry for rebalancing production, consumption, savings, and interest rates in the United States and all over the industrialized world.