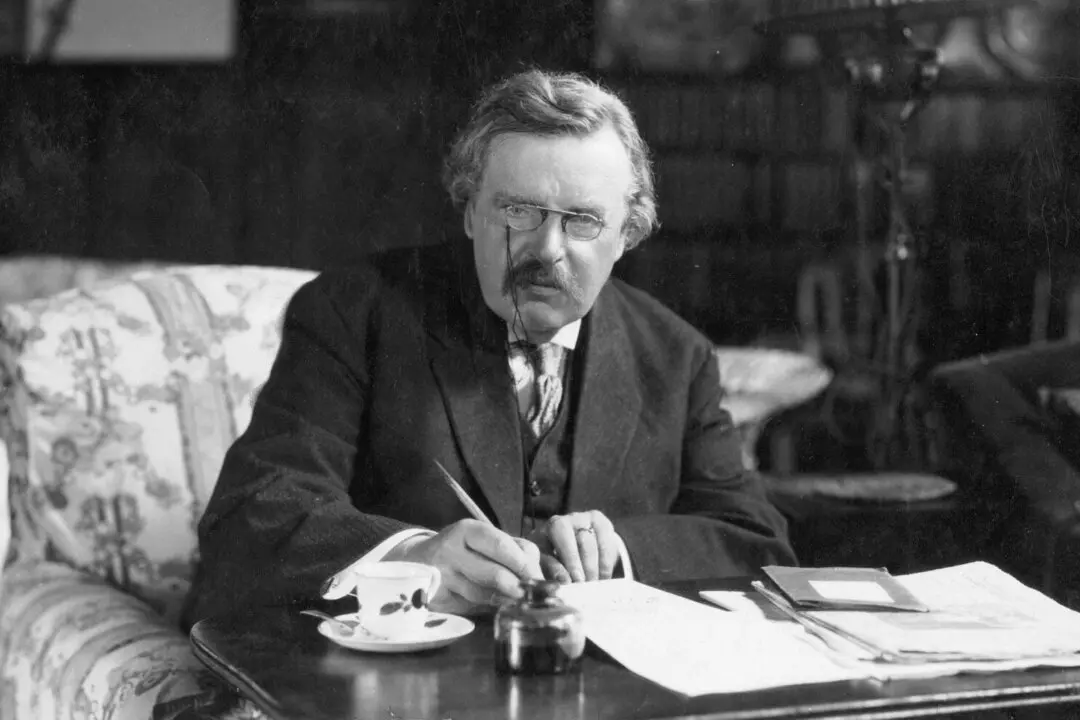

Commentary

There was a time when gratitude was regarded as the essence of our humanity. The Roman statesman and scholar Marcus Tullius Cicero once said, “For this one virtue [gratitude] is not only the greatest, but is also the parent of all the other virtues.”