Commentary

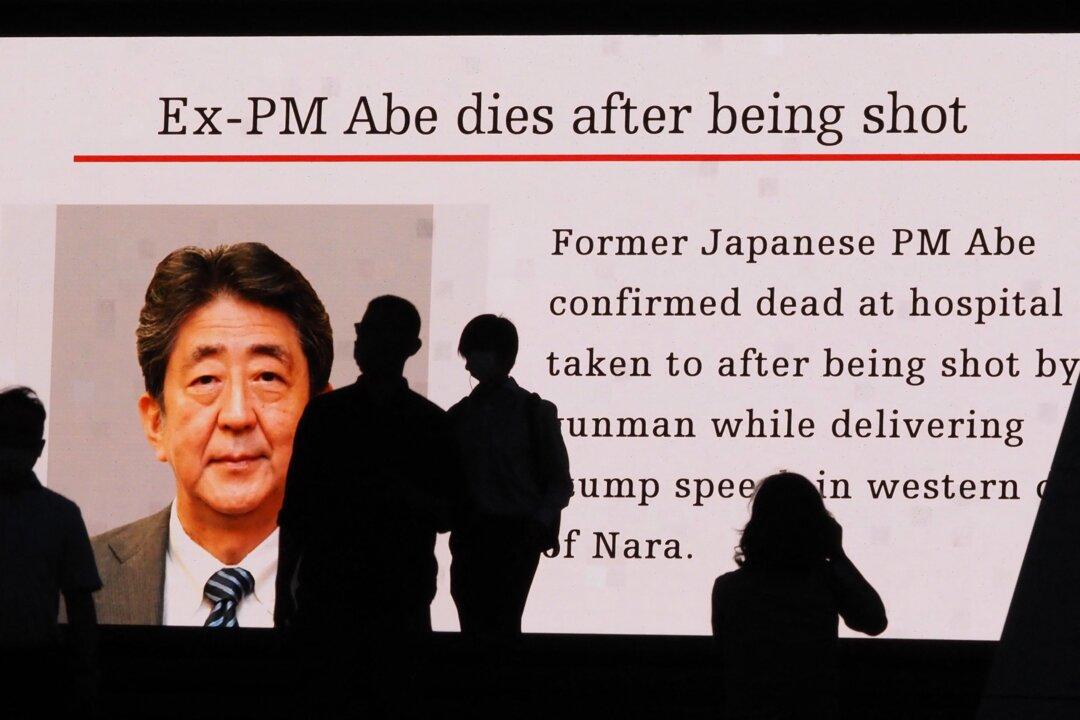

Statesmen come along only once in a great while. Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who was assassinated on July 8 in Nara, Japan, was a statesman.

Statesmen come along only once in a great while. Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who was assassinated on July 8 in Nara, Japan, was a statesman.