Commentary

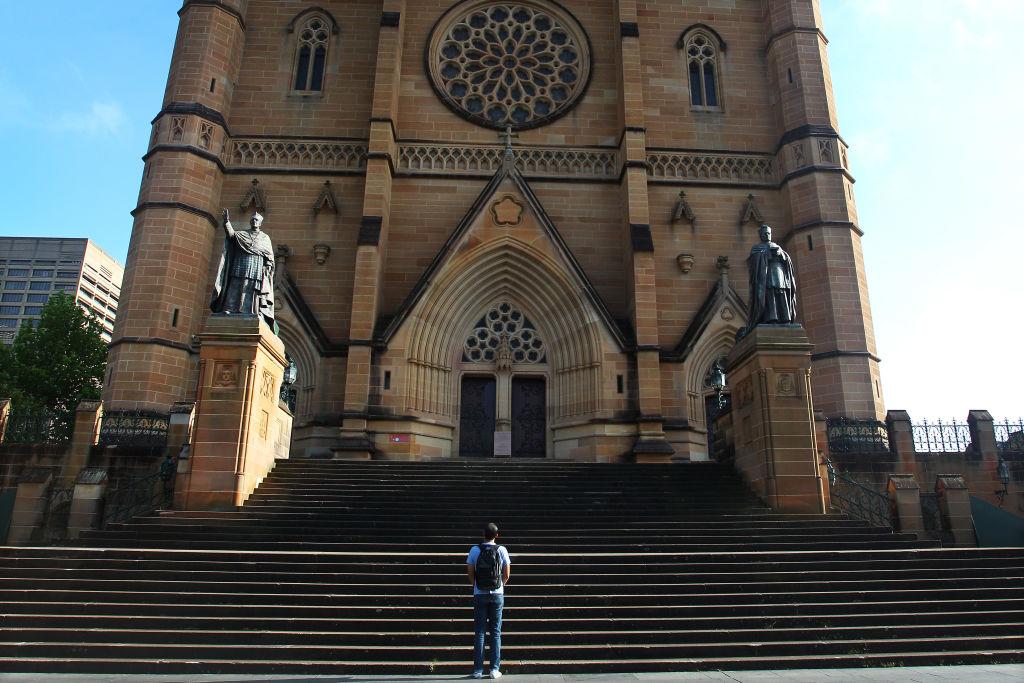

In the last sitting weeks of the Australian Parliament, the political landscape focuses on the Religious Discrimination Bill introduced by the Attorney-General, Senator Michaelia Cash.

In the last sitting weeks of the Australian Parliament, the political landscape focuses on the Religious Discrimination Bill introduced by the Attorney-General, Senator Michaelia Cash.