Commentary

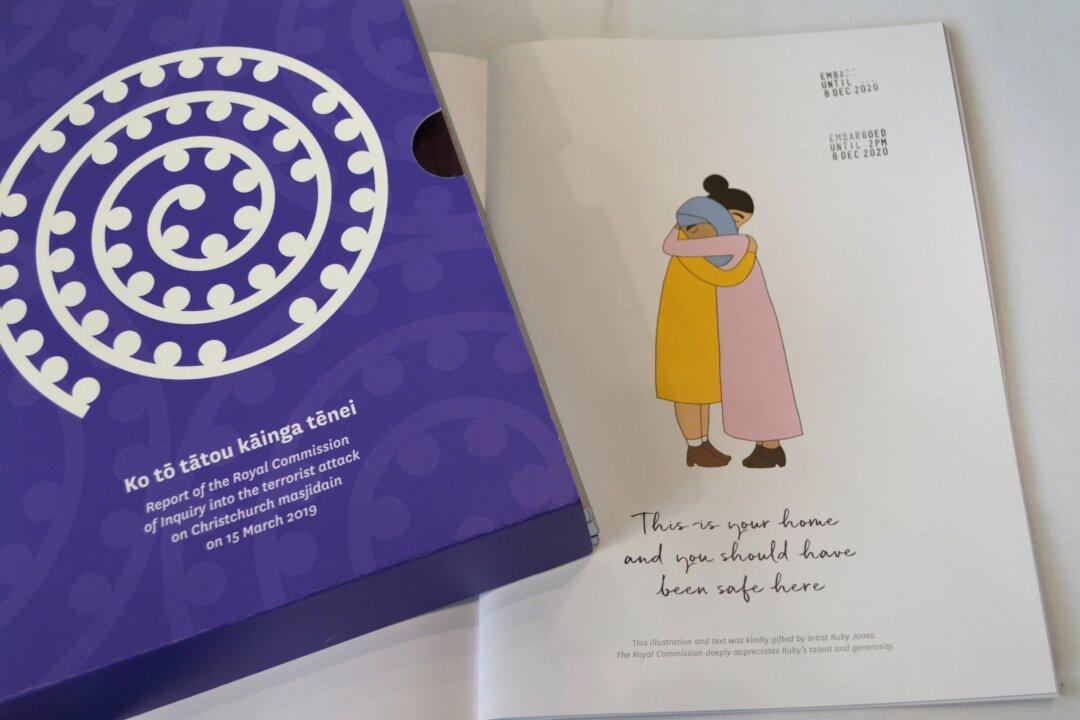

On March 15, 2019, a terror attack at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand claimed 51 lives and wounded another 40 people. A NZ Royal Commission has now released a massive report on the attack, more than 800 pages, the most important point of which is that the terrorist was unknown to authorities until moments before he struck, but that somehow more and better intelligence would help prevent future attacks.