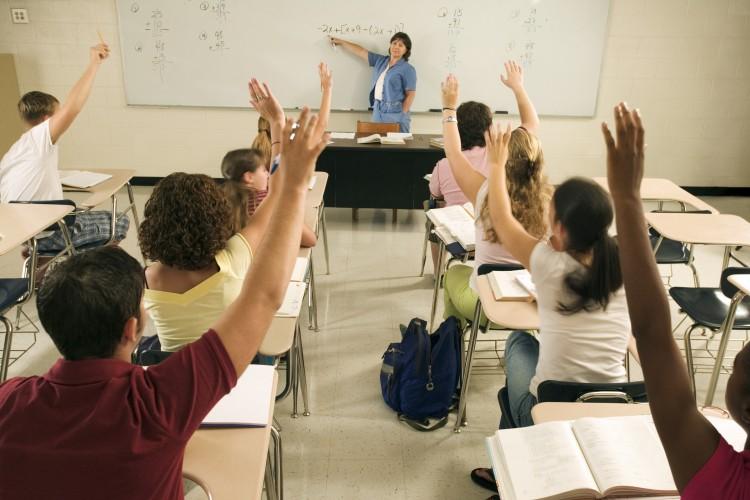

Suppose you have two students. One comes home with a mark of 95 percent in science while the other gets 80 percent in the same subject. It’s not hard to figure out which student is probably doing better. Percentage grades are so simple that virtually everyone can understand them. That’s why they appear on many report cards in Canada and around the world.

Now let’s compare the same students under a different reporting system. Instead of a single percentage grade for each subject, students are given a score of 1 to 4 for several different outcomes. In this case, both students receive a mark of 4 in categories such as “analyzes and solves problems through scientific reasoning,” “develops skills for inquiry and communication,” and “explores scientific events and issues in society.”