Commentary

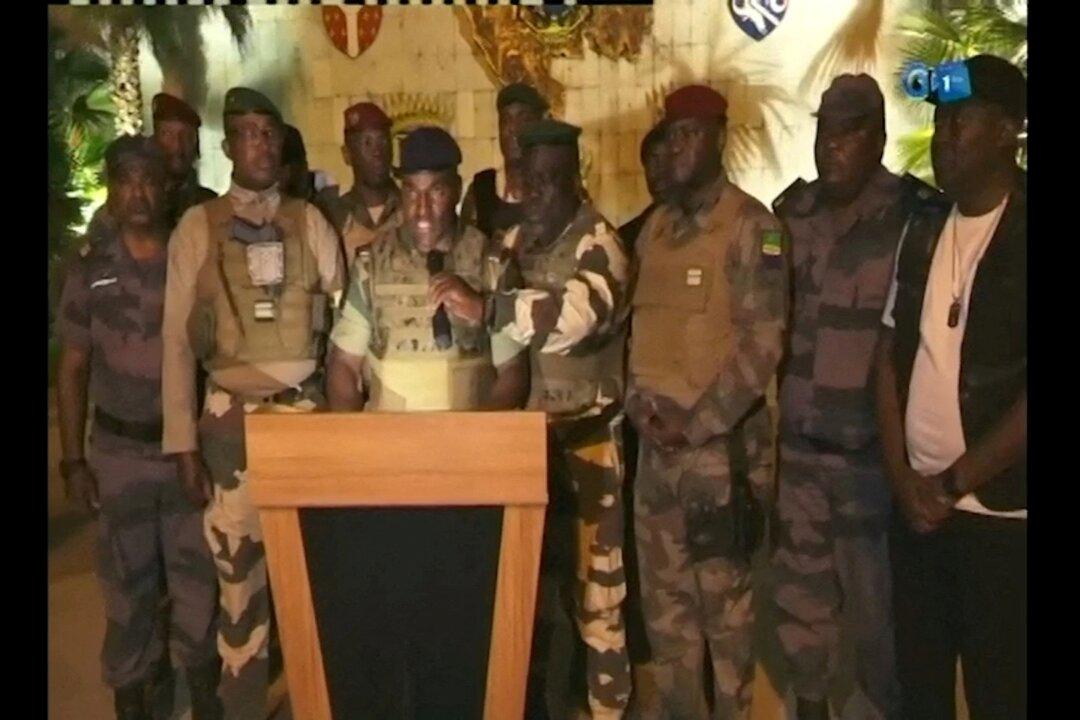

A change of rulers is the joy of fools, goes the old Romanian folk saying, and I recalled it as I saw pictures of rejoicing crowds in the street after the recent military coups in the West African countries of Niger and Gabon.

A change of rulers is the joy of fools, goes the old Romanian folk saying, and I recalled it as I saw pictures of rejoicing crowds in the street after the recent military coups in the West African countries of Niger and Gabon.