Commentary

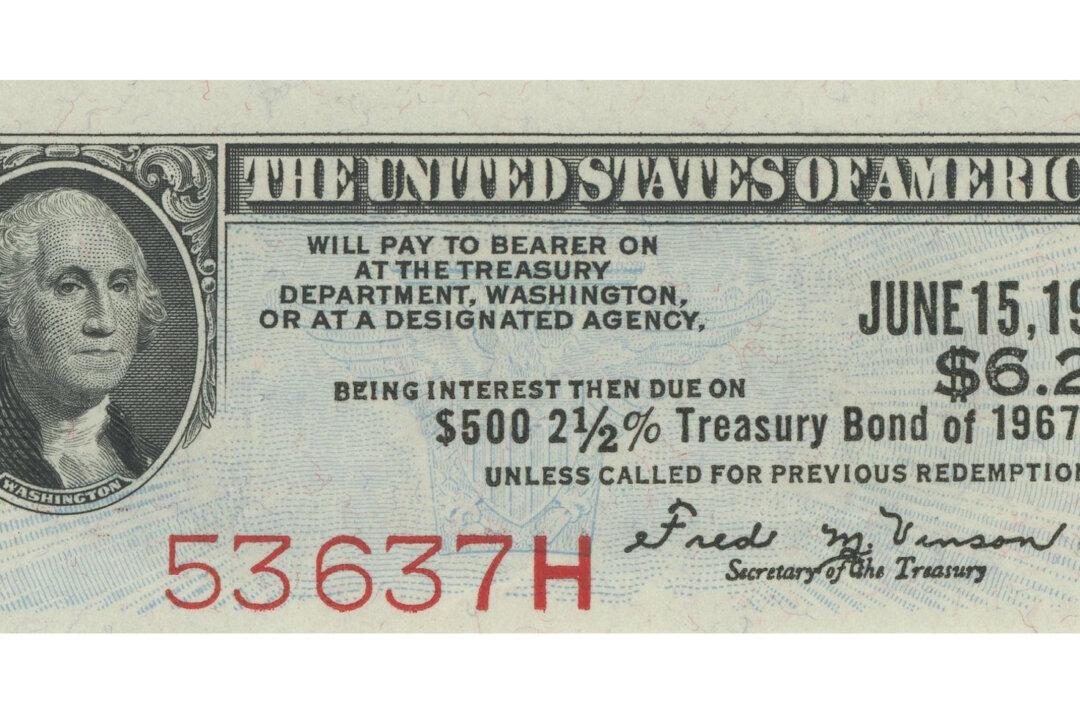

The total public debt of the federal government surpassed $35 trillion last summer and continues to climb. As outlined in the AIER Explainer, “Understanding Public Debt,” a wide variety of investors purchase U.S. Treasury notes financing this debt.