Commentary

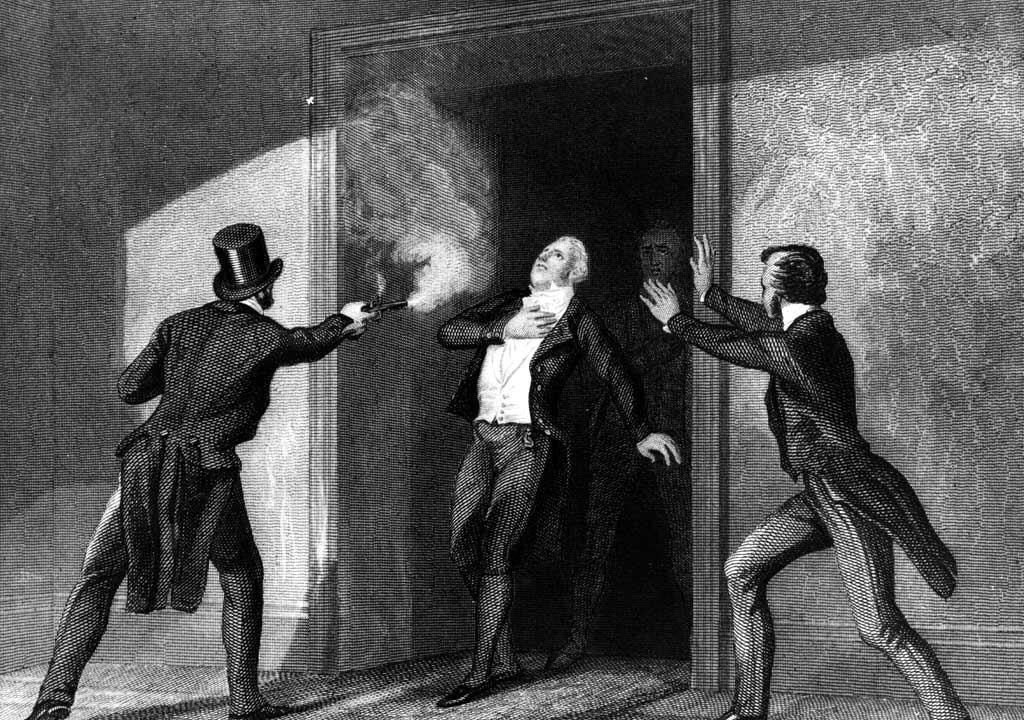

One of the greatest difficulties in maintaining a stable democracy is keeping one’s political leaders from being murdered.

One of the greatest difficulties in maintaining a stable democracy is keeping one’s political leaders from being murdered.