Commentary

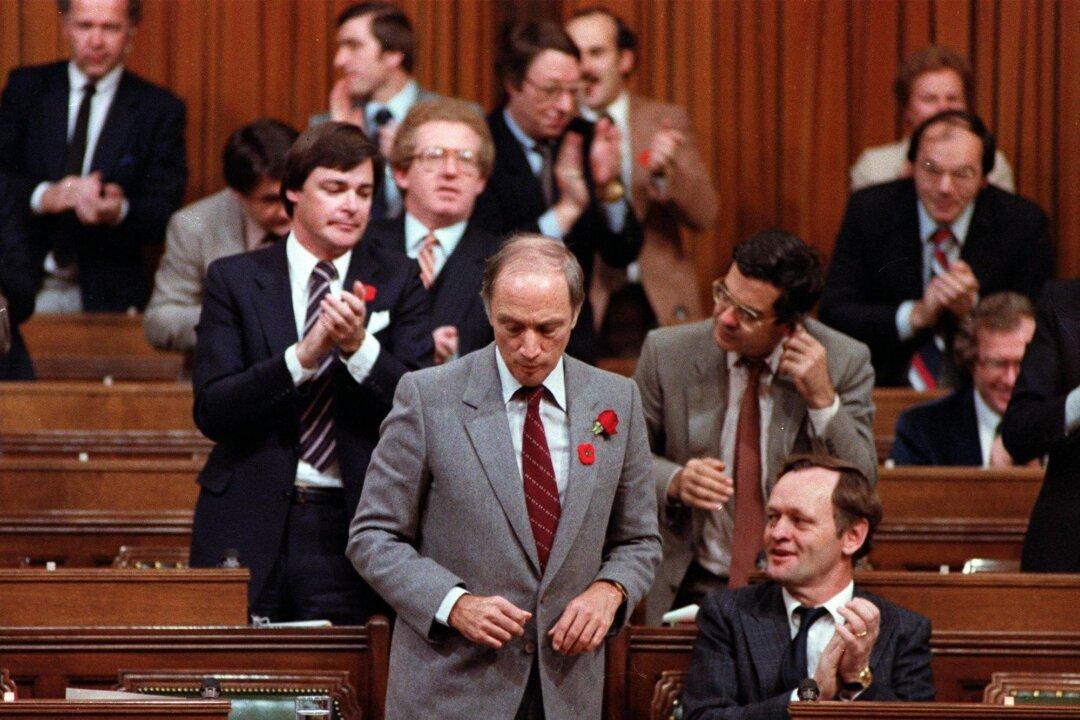

Former prime minister Pierre Trudeau has been described by some as a brilliant philosopher king. With decades now having passed since his tenure, it’s worth examining whether the impact of his policies matches that description.

Former prime minister Pierre Trudeau has been described by some as a brilliant philosopher king. With decades now having passed since his tenure, it’s worth examining whether the impact of his policies matches that description.