Commentary

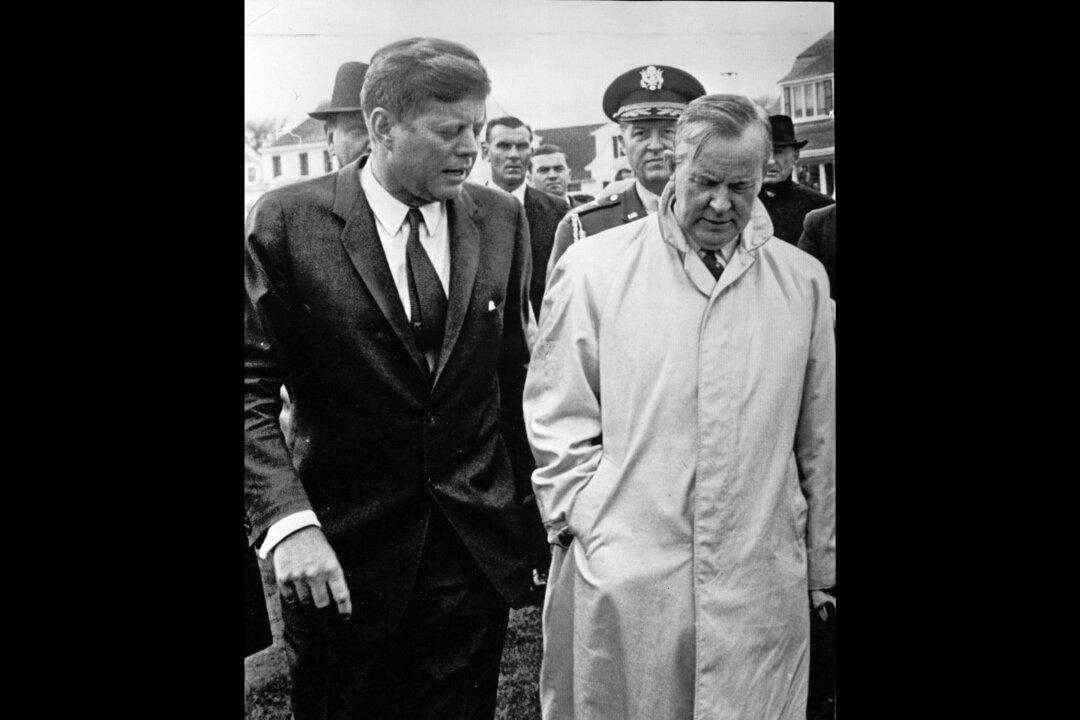

In troubled times, it can be helpful to ponder the thoughts of learned people of compassion and action. Lester Bowles Pearson in Canada and John Fitzgerald Kennedy in the United States were two such people.

In troubled times, it can be helpful to ponder the thoughts of learned people of compassion and action. Lester Bowles Pearson in Canada and John Fitzgerald Kennedy in the United States were two such people.