Commentary

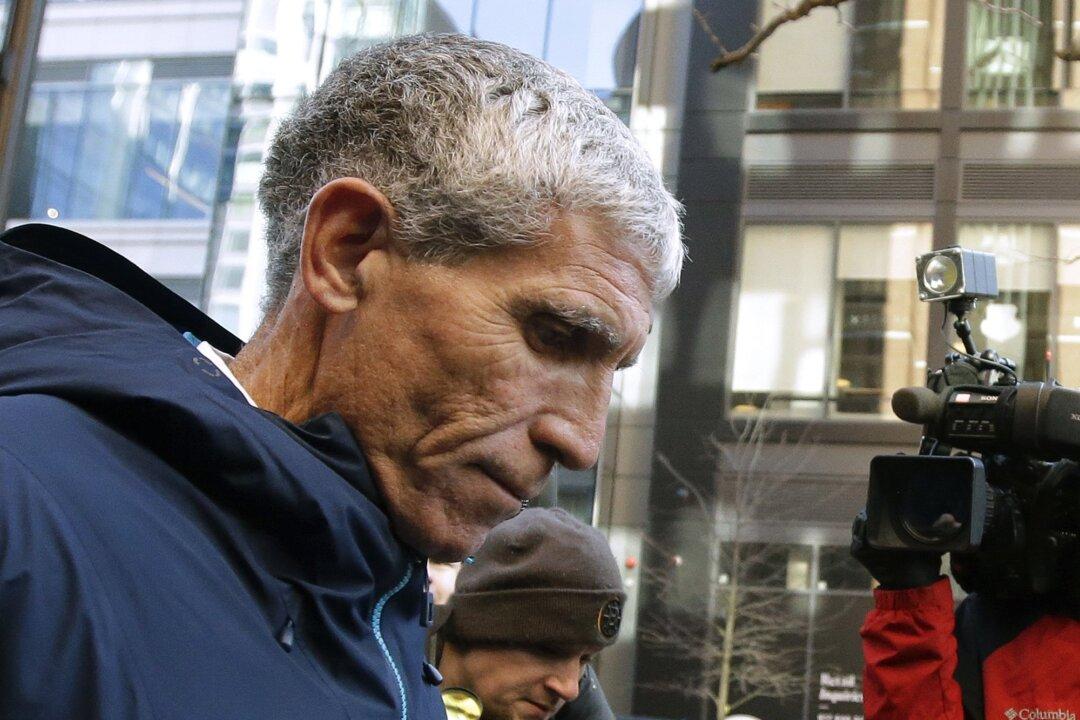

The elite university admissions scheme scandal broke on a Wednesday. By the following Saturday, The Wall Street Journal had published 21 articles about it.

The elite university admissions scheme scandal broke on a Wednesday. By the following Saturday, The Wall Street Journal had published 21 articles about it.