As I watched the military parades at the start of Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee celebrations on June 2, I was full of admiration for the men and women in uniform who not only marched and played music with remarkable precision and discipline, but whose very purpose was to defend us as a country and our values of freedom, democracy, the rule of law, and human rights.

They answer to a civilian, democratically elected government and a monarch who, although unelected, embodies both in her role and in her character a constitutional assurance to safeguard our democracy.

Tens of thousands of people joined the celebrations in London’s parks and streets, and millions more participated across the UK and around the world. I was surprised to learn through media commentary that the Commonwealth, a network of 54 countries with the queen at its head, represents 2.6 billion people, almost a third of the world’s population.

But as we mark the extraordinary 70th anniversary of the queen’s coronation, my thoughts quickly turn to another anniversary that we commemorate today, the Tiananmen Square massacre in Beijing on June 4, 1989.

To paraphrase the title of Charles Dickens’s novel “A Tale of Two Cities,” this weekend, the world focused on a tale of two armies: the British Army, with the queen at its head, the epitome of public service and duty, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) dictators in charge, the embodiment of repression, inhumanity, cruelty, mendacity, impunity, and criminality.

No one would suggest that the British army is perfect—but the difference is this: It’s accountable to the people through our democratically elected leaders, the system addresses acts of wrongdoing, and its objective is to protect the country, its people, and its values, not a political party or an ideology. By contrast, the PLA’s name is a misnomer. It’s against the people and against “liberation.” It should be renamed “the People’s Repression Army.”

That’s why it’s so vital that we remember the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, for three reasons.

First, the CCP is trying desperately to make us forget. Across China, generations of people have grown up since 1989 with no knowledge of the scenes of barbarity that occurred in Tiananmen Square, the surrounding streets, and in cities across the country on June 4 that year.

The butchers of Beijing and their successors in Zhongnanhai have censored news, spread propaganda, and brainwashed people so successfully that many people genuinely don’t know, and those who do are afraid to remember.

Some activists, such as lawyer Chow Hang-tung, are serving long jail sentences for organizing such vigils. Last year, no formal vigil was permitted, but Catholic churches held masses, and Hongkongers flashed their mobile phone torches as a sign of remembrance.

This year, the Catholic Church in Hong Kong has said it won’t hold any masses, and the police closed Victoria Park, warning that even visiting a park on June 4 could be a crime. Illegal gatherings could result in five years in prison. Presumably, flashing a phone torch light is risky, too.

Late last year, all remaining symbols of remembrance for the Tiananmen Square massacre—the Pillar of Shame, the Goddess of Democracy, and other memorabilia—were torn down and banned. Beijing wants to erase the memory of the June 4 massacre, even in Hong Kong.

Despite this, some brave Hongkongers still found ways to mark the anniversary. Miniature figurines of the Goddess of Democracy were hidden around the campus of the Chinese University of Hong Kong in defiance of authorities.

That’s all the more reason why we who have freedom outside China must ensure that the spotlight remains on the June 4 anniversary. Later today, I'll be speaking at three different rallies in London at key landmarks: outside the prime minister’s residence in Downing Street, Piccadilly Circus, and outside the Chinese embassy. We must not be silenced.

The second reason we must keep the spotlight on the Tiananmen Square massacre is simply this: We should have learned the lesson in 1989 that a regime that turns its guns on its people is not a regime to be trusted, respected, or legitimized. It says a lot about the nature and character of a regime if it’s prepared to slaughter thousands of peaceful protesters in full view of the world.

Until recently, we failed to learn that lesson. For a time, many of us, myself included, thought we saw signs of liberalization in China in the 1990s and early 2000s. I traveled more than 50 times in China throughout that period, including living in China several times for short stints and living in Hong Kong for the first five years after the handover. I made many Chinese friends—including human rights lawyers, bloggers, religious leaders, and civil society activists—who appeared at the time to have a certain amount of space and who themselves felt cautiously optimistic that it might expand further.

[embed]https://twitter.com/benedictrogers/status/1532852121674174464[/embed]

Few of us were so naive as to not understand that the CCP was always repressive, but it did appear that, for a while, the red lines had become more distant, and space for some degree of free thought had expanded. Over the past decade of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s rule, that view has been entirely reversed, as literally all that space has been shut down and many of its inhabitants have been locked up.

In China today, there are slow-motion June 4 massacres taking place all the time. Not with tanks and guns, but with repressive laws, prison camps, surveillance technology, and instruments of torture.

I was denied entry into Hong Kong in 2017, have received numerous threats to myself and my mother over recent years, and have been warned by the Hong Kong Police Force officially that I could face jail in Hong Kong if they could get their hands on me. That doesn’t worry me because there’s little they can do as long as I don’t get extradited, but it illustrates the dangers for Hongkongers, Uyghurs, Tibetans, and mainland Chinese-exiled dissidents. If the CCP is willing to threaten a foreign activist in this way, the dangers for those it regards as “its own people” are even greater.

And that leads me to my third reason why today’s anniversary matters. We must always learn from history. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has surely taught us that. A regime that’s allowed to massacre thousands of people with impunity is not only a threat to its own people—it becomes a threat to us.

All dictatorships are like bad drivers with one eye in the rear-view mirror. If no one tries to pull them over for their speeding or drunken driving, they’ll carry on, causing carnage. Until now, for 33 years, the rest of the world has failed to keep the CCP in check—and as a result, the regime has been emboldened. That’s why today we have a Uyghur genocide, the total destruction of Hong Kong’s freedoms, the continued tragedy of Tibet, religious persecution, organ harvesting, and the all-out assault on civil society in China.

For my new book, “The China Nexus: Thirty Years In and Around the Chinese Communist Party’s Tyranny,” which will be published in October, I interviewed several prominent activists and journalists who were in Beijing on June 4, 1989. Their stories are consistent.

Yang Jianli, a prominent exiled Chinese activist, told me that in the early hours of June 4, he and his colleagues cycled into the square.

“We saw the troops open fire, and we saw many people killed,” he told me in an emotional online call. “It was so hard to believe. I saw tanks moving at high speed, tear gas, machine gun fire, and I heard so much screaming. That was what propelled me into becoming an activist.”

Veteran Canadian journalist Jan Wong, author of “Red China Blues,” who was in Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, told me what she saw firsthand.

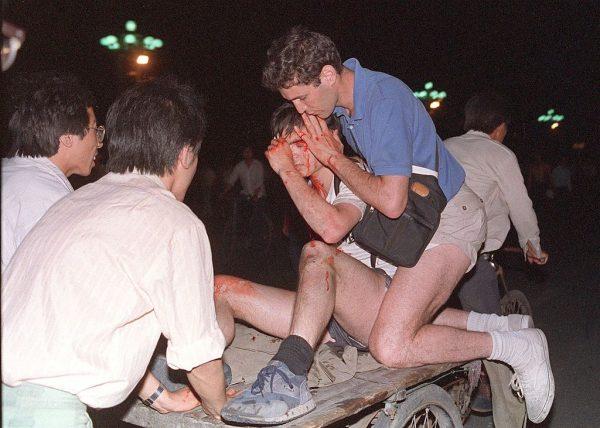

“They were shooting, people were running, and people tried to rescue others,” she said. “They brought out bodies on bicycle seats and pedicabs. They just ran into gunfire.”

Later that night, Wong herself narrowly missed a bullet fired into the wall of the Beijing Hotel, just inches from the balcony where she was standing observing the carnage.

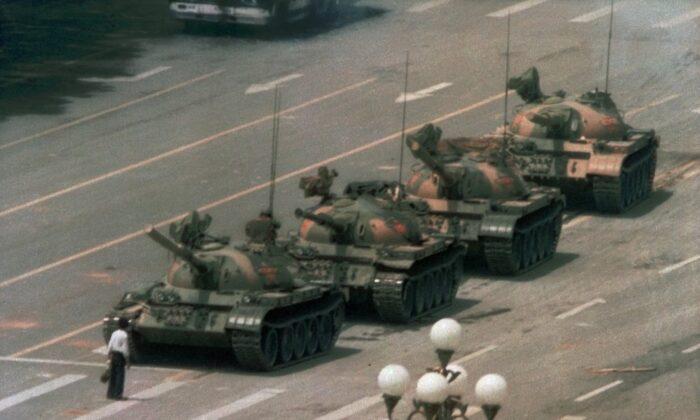

She saw the infamous “Tank Man” scene in real-time.

“The army had been running people over, and I had watched the tanks. Then my husband pointed to this man standing in front of a tank. ... I saw this whole dance between ‘Tank Man’ and the tank. He tried to stop the tank like a soccer goalie. Then he climbed onto the tank, tried to talk, then climbed down again,” Wong said. Then he “melted into the crowd.”

In addition to “Tank Man,” she believes that the tank driver was a “real hero” because he refused to run the man over.

I believe we need to do three things going forward.

We need to ensure that history keeps a record so that—despite Beijing’s best efforts—the massacres of 1989 aren’t forgotten and that one day the cause for which so many gave their lives prevails in China: freedom, justice, peace, and truth.

Then we need to try to find the “tank drivers” in the regime who refuse to run people over. As hard as it may be, we have to do to the CCP what they do with such skill to us—we must pursue a divide-and-rule policy and cause them to split.

And at the same time, we must create a united front to fight their “United Front.” Unity doesn’t mean uniformity. We can welcome and respect the diversity of thought, strategy, tactics, and approach. But we should endeavor to encourage a “unity of spirit and purpose.”

Egos and rivalries should be set to one side, with personal agendas suspended, and everyone who opposes the regime in Beijing should find a way to work together—or at least not work against each other. Only when we do that—and create our own “United Front”—can we have a hope of advancing.

Thirty-three years on from the massacre, let’s not allow China’s fallen heroes to be forgotten. Let’s remind the free world, as a large part of it celebrates an icon of human dignity—the queen—this weekend, of the big challenge that faces us ahead in confronting the problem of the CCP. Action on that front would go some way toward respecting the legacy of those who stood—and fell—in Tiananmen Square in 1989.