Commentary

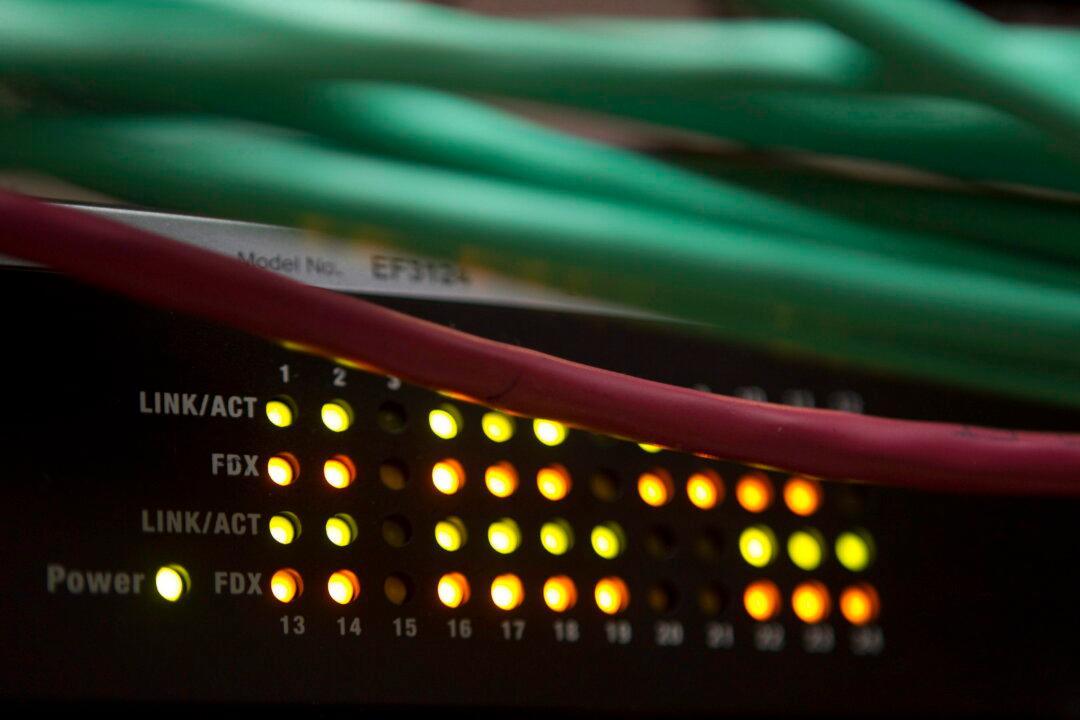

In 2017, late-night host Stephen Colbert told his audience that it was “a sad day” because the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had voted to repeal Net Neutrality, an Obama-era rule that required internet service providers (ISPs) to offer “equal access” and speeds to all lawful websites and content regardless of their source, and prohibiting “fast lanes” for certain content.