Commentary

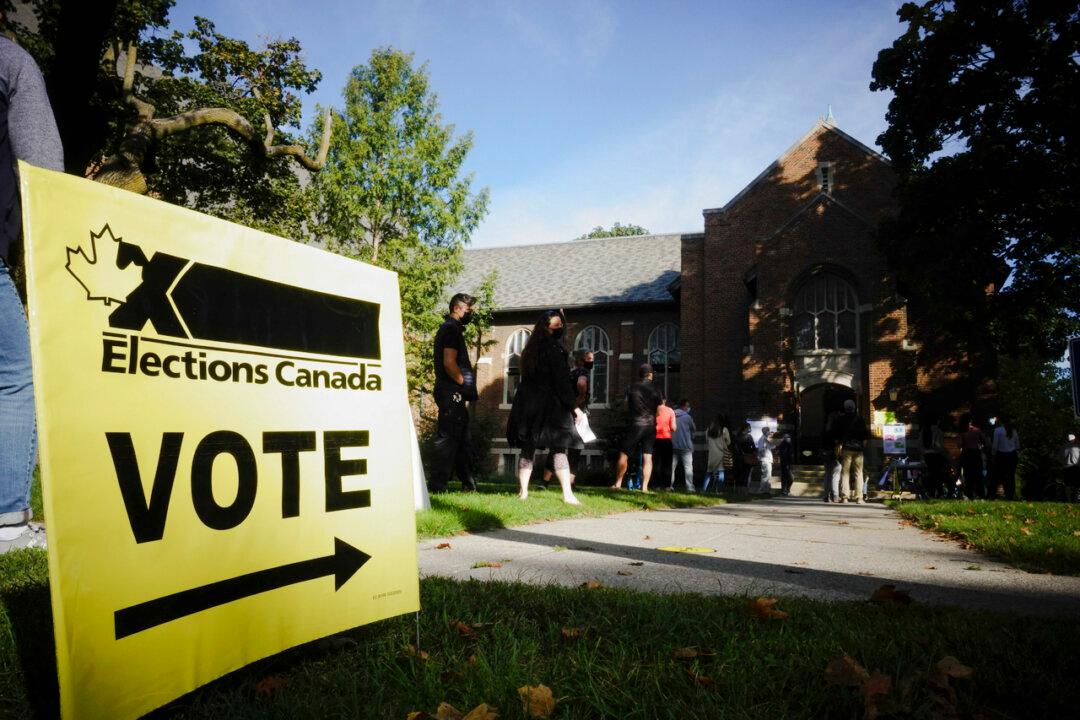

Voters often approach general elections and byelections with a different lens. The former is a specific vote that can contribute to a government’s election or re-election. The latter can be a multi-purpose vote to send a message about the satisfaction or dissatisfaction of a government, party, leader, or the political process.