Commentary

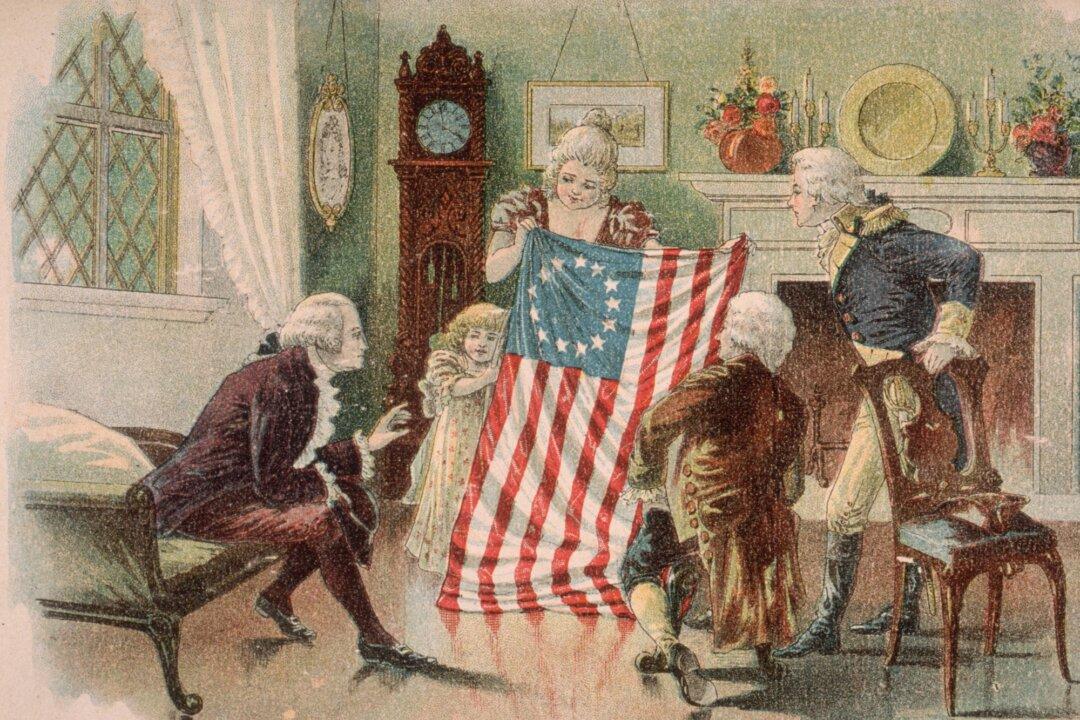

Once a fabric begins to fray, the continuing weakening of the garment is almost inevitable. Each stress, each tug, further weakens the bindings of the cloth. Unless the tear is mended before it gets too far, the garment won’t last long.

Once a fabric begins to fray, the continuing weakening of the garment is almost inevitable. Each stress, each tug, further weakens the bindings of the cloth. Unless the tear is mended before it gets too far, the garment won’t last long.