Commentary

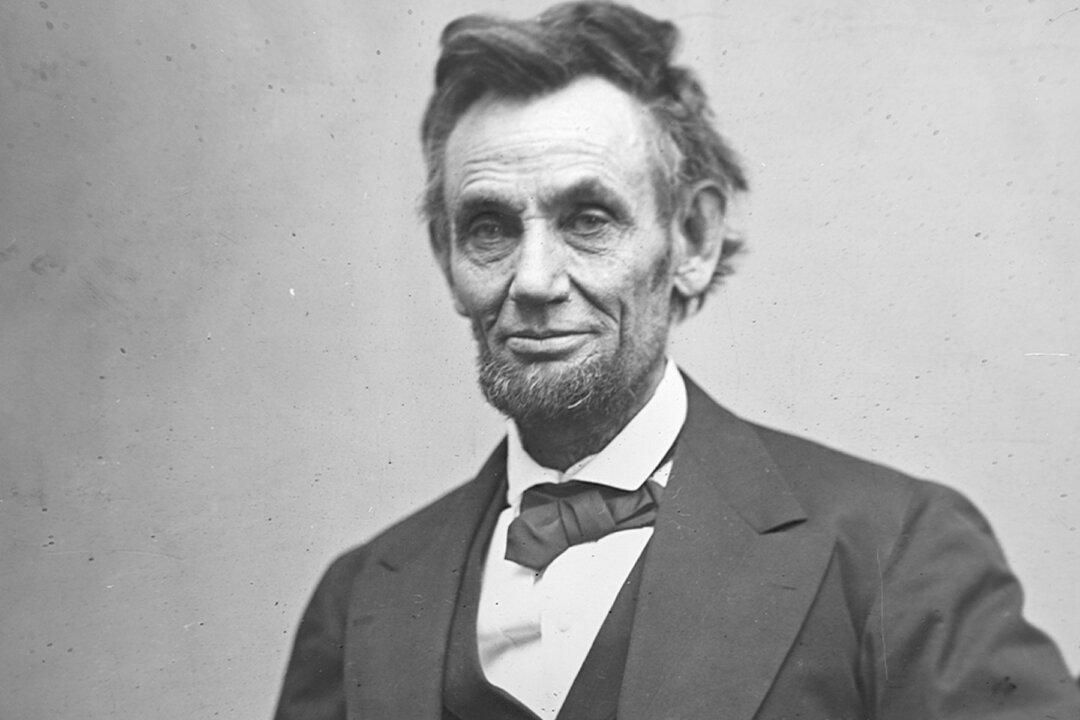

Abraham Lincoln believed that the success of American self-government required the right ideas and the right institutions. He thought that the right ideas were found in the Declaration of Independence—specifically, human equality, individual rights, government by consent of the governed, and the right of revolution. A corollary to these bedrock principles was “the right to rise,” which Lincoln described as the duty “to improve one’s condition.” These ideas of the Declaration were so fundamental that Lincoln referred to “the principles of Jefferson” as “the definitions and axioms of free society” and “the father of all moral principle” in the American people.