Commentary

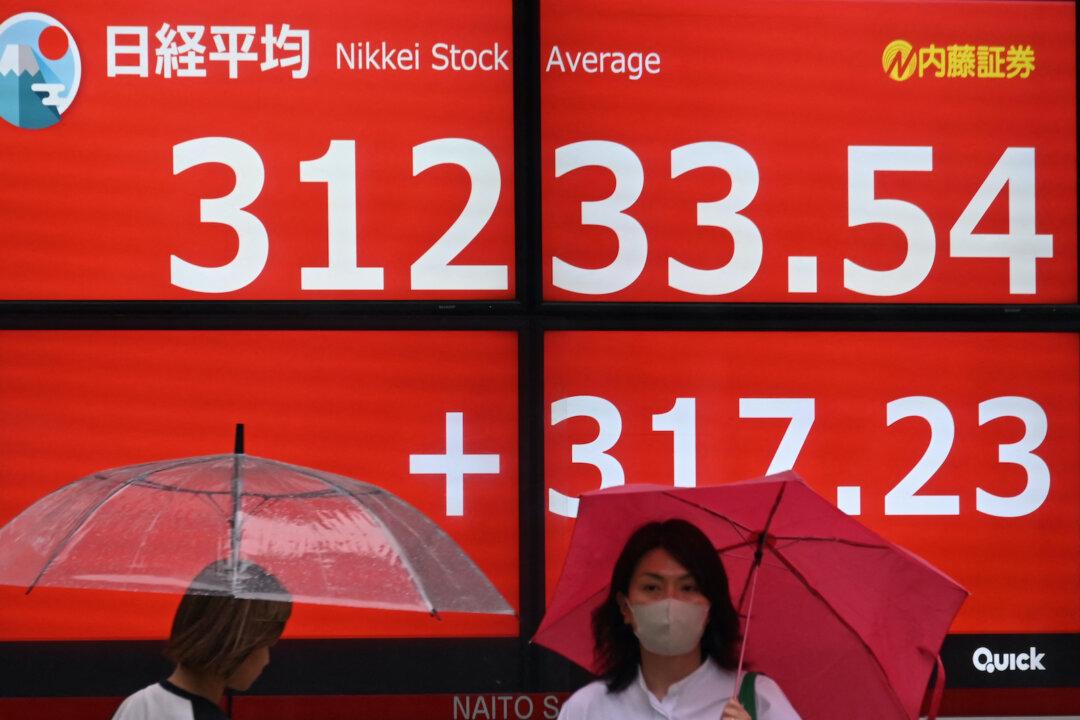

Japan appears to be a reemerging star in Asia. Market focus is two-fold, Japan’s stock market performed brightly, and the Bank of Japan might turn monetary policy from easing to tightening. Behind these, Japan’s old problems are still there. Population is still on a downtrend and is actually decreasing faster than before. Another famous problem is the government’s gross debt-to-GDP ratio, which is still on an uptrend albeit at a steady accelerating pace. Culturally, corporate inefficiency and the glass ceiling are still there and do not show much improvement.